The Words and Things of Chung Seoyoung: Luminous Evidence in the Concentration of Ambiguity

Objects endeavoring on their own not to collapse, and through plentiful language appearing and shining endlessly from within our tense relationship to our age; sculptures that overstep the boundaries of their own material and move us through differentiated thought and cognition. How is such a world of objects or sculptures possible?

In today’s society preoccupied with the kind of political art that expresses concrete views of geopolitical, social, and political discourse, it seems that it is becoming a taboo to use the term “political” when discussing sculpture. This is because the aesthetic territory of sculpture—in which one must speak of the relationships and structures of matter and material, shape and form—is easily conservative and has a tendency to recognize “artistic objects” as objects easily-accepted into capitalist distribution networks. So-called political art endeavors, as much as is possible, to avoid being absorbed into this capitalist state by minimalizing materiality, focusing on intellectual production, or maintaining its distance from aesthetics; it beco- mes defensive. But either way, if we recall how the political art of the past has been taken in by the market—rather than being able to defer its absorption—we see how in a materialist world “all that is solid melts into air.” If this is the case, we must return to the question of what challenges, even, are still available through sculpture. Can sculpture indeed no longer be radical?

The artist Chung Seoyoung lightly disregards this question. This is because for the artist sculpture is above all radical and belongs to the space of political thought. Though she has expanded into sound and other various media, the origin of the artist’s work lies in sculptural objects. The artist, earnestly grounded in the present time, considers the essence of the relationships between objects and language and draws conclusions in a sculptural state. This is not the creation of a simple material end or a process of aesthetic compromise. Chung’s task is still clearly in the completion of a luminous personal politics that does not collapse under the name of sculpture.

The artist, through her clear awareness of objects thick with conventional and quotidian language in our society, transforms speech and language in a new, creative space. Objects that do not describe objects and a radical understanding of language that confirms the absence of objects reverberate from within her works. Chung’s sculptures become the most political objects through the most moderate and traditional artistic methods. Though this is accomplished by means of material, Chung’s sculptural language exposes a language that is not embedded within material and reveals the intact politics of art without dealing with real political issues. In this way, her works exist as solid objects that do not vanish. This is the reason why we must now revisit Chung’s work.

Sentences that Push Aside the Pressure of Meaning, Between Ambiguity and Secrecy

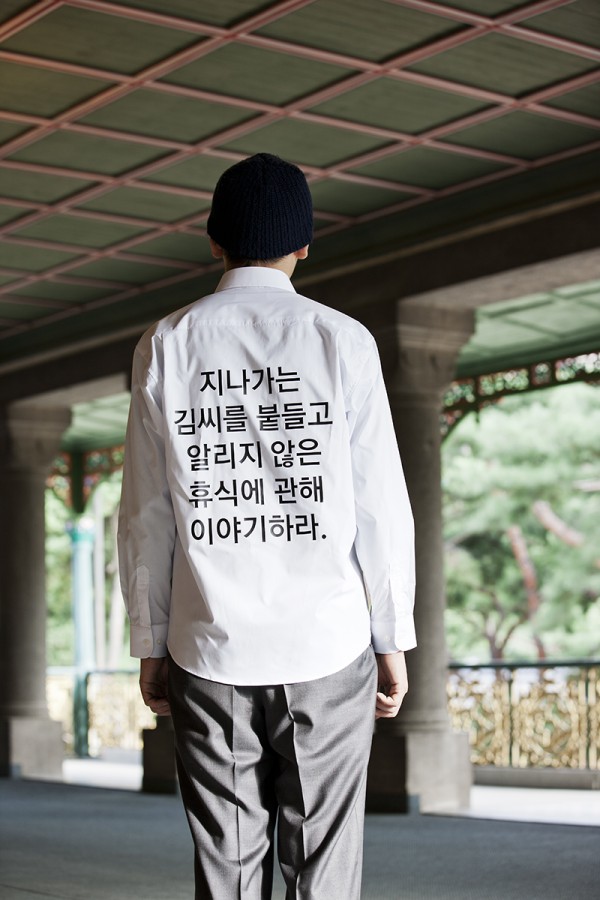

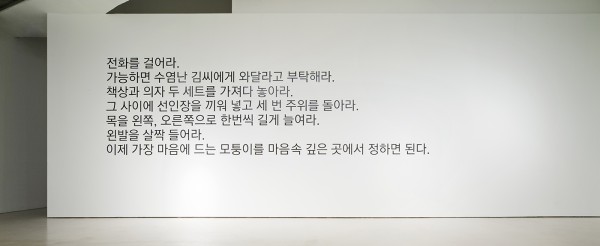

The words that appear in Chung’s work often sounds perplexing. These appear in the forms of sentences in text drawings or as the titles of sculptural objects made by the artist. In fact, until the beginning of the 2000s, the short words that appeared in the titles of works gradually evolved into sentences. However, these sentences, rather than helping one understand a certain meaning, tended only to describe situations. The following phrases were on the walls of the recent 2012 exhibition at Gallery Hyundai: “Dial the phone. If possible, ask the bearded Mr. Kim to come. Bring two sets of chairs and desks. Put a cactus between them and walk in a circle around them three times. Make of long stretch of your neck once to the left, and once to the right. Lift up your left foot slightly. Now all you have to do is decide from deep inside your mind the most pleasing corner.” The sentence “Stop Mr. Kim as he passes by and talk to him about unannounced rest” was written on the back of a performer who wandered around the inside of the Jeonggwanheon1 at Deoksu Palace. Such phrases also often appear in Chung’s drawings, for example: “The sum total of what gradually becomes lumpier and what gradually becomes clearer” and “What looks the largest below a bluff, what comes gradually closer and splits into two.”

Usually when one reads a sentence their goal is to grasp the meaning it conveys. However, it seems impossible to grasp sentences like these with such a goal in mind. All we can do is concentrate on the situations they describe and make related associations. The first two sentences seem to instruct certain actions. However, we cannot be sure if these are orders given to another person or instructions addressed to one’s self. On the other hand, the latter two sentences appear to be describing something’s state or movement, though they are essentially ambiguous. In short, they are scenes of situations; it is unimportant whether or not these situations are real. The only thing that is clear is that these sentences are in the realm of the uncertain and do not convey a definite meaning.

Another thing that is evident in these sentences is, in the first two phrases, that there is a subject who must carry out a certain action, and in the text drawing, that the phrases are about some object or the state of some thing. Drawing from the methods of these two kinds of sentences, let us try to summarize the subjects’ actions and the state of the objects. What can we make of this? If we admit that these sentences at least came from the artist and project from the artist’s world, we can say that the world in which “there is some subject who acts and an object in some state” is the world that exists between the artist and the work. It could be, at least, that these sentences relate to objects purely and apart from the outside world’s systems of value and meaning; they could come from the undisturbed time of the artist who deals with objects. This private time is the time of some ceaseless exercise, the secrecy of an extremely physical world in its conduct, and a moment that cannot be reduced to one meaning.

In order to approach Chung’s considerably vague sentences, one should in fact set aside words, the sentences’ symbolic function, the discovery of outside meaning, one’s obsession with message and instead stubbornly gaze. Whether the work consists of a sentence, a sculptural form, or composed objet, ultimately the viewer can only enter into the work through this process of thinking based on the relationships between the details discovered within a single work, the entire composition formed by articulated elements and their connections, and these elements’ situation or formal modality. In the process of continuously entering into the sentence and emptying it out something seems to appear like a light discovered in the dark, but in fact that thing once again departs and approaches in repetition. Because the meaning of Chung’s work endlessly operates in an unstable state, it is hard to grasp the work’s meaning through an outside system of symbolic language. This is not just a difficulty; it is an important feature of the work. Normally when the audience views a work of art and intends to confirm its message or meaning, the artist rather recognizes humans’ obsession with creating meaning—and the world of that violent meaning—and constantly pushes it away through her words and objects.

Epistemological Words and Things

The exhibition Lookout (2001) at the Artsonje Center showed the artist’s performative language; not only was the show a beginning point in this regard, it also left the most intense and unfamiliar impression on the Korean art world between the beginning of the period of “contemporary art” in the late 90s until the early 2000s. The exhibition was a theatrical space of signifiers that were not their signified; the viewers, faced with these signifiers that had already departed from their meaning, had to confront a new difficulty they had not yet experienced in previous local exhibitions. Even at that time, the pressure to read art as conveying a message was predominant among the majority of the art-viewing public, including experts and non-experts. Because of this, Chung’s works in the exhibition space—which could not be grasped as symbols of a certain message or meaning—were indeed tremendously rebellious and political.

The things placed in the exhibition space at this time were sculptural objets consisting of floor coverings, sponges, wood, clay, glass, floral foam and other industrial materials that offered different, that is, abnormal experiences of objects. For example, Flower (1999), Lookout (1999), Gatehouse (2000) and other works were miniatures of ambiguous scale that imitated—while at the same time not imitating—the images of the words in their titles; The Sculpted Bride (1997) and Athletic Flower Arrangement (1999) and others were installation works that were each translated into forms based on their strange titles but did not depict images. Park Chan-kyong, who wrote for the 2000 exhibition catalogue, explained the particularity of the artist’s work through the example of Flower.

“As in the case of Flower (1999), what is imitated here is not so much the living flower as a real object, but the word “flower.” The moment the flower acquires sound and meaning, or to follow Saussure, once it belongs to an abstracted system of language, “flower” will lose its vivid concreteness; what Chung aims for is exactly the subjective and creative effort or mystery that one can say is the inevitable result of linguistic imitation, the death of the vivid concreteness originally possessed by the objects issued by language, and the “speech” attempting to break out of that system.”2

In fact we can say, as is already said in linguistics, that the meanings of words and the relationships they create are arbitrary. The word “flower” is just a word chosen to designate this thing (flower); because of this, a flower is not a priori endowed with the word “flower.” In fact, in the end the word “flower” is no different than the absence of the flower. The moment we think of the word “flower,” we see the advent of a subjective “flower” since what comes to mind for each person is different. Ultimately, this flower which is not a flower is of the world of the Derridean notion, ‘différance.’ Also, the above-mentioned “death of the vivid concreteness originally possessed by the objects issued by language” describes exactly the incorporeal “speech from objects” confirmed by words; one can say it is the object-ness of the signifier.

Here we need to try to understand how words come into connection with Chung’s objects. They break free of the structural function of language that mediates between humans and objects. The structural function of language is “the function of unifying and generalizing an object under one symbol; for example, as we group together different dogs under the term “dog,” [it is] the function of prescribing and identifying general attributes (identification based on given meaning)”; this function is formed through the one-sided relationship between the subject (human) and object (thing). Inversely, Chung’s sculptures disturb and disperse the normal symbols of the object objectified by the human subject. That is, her Goose (2007) looks like a goose but is not a goose. Her Lookout (1999) looks as if it possesses the ability to view but, with its ambiguously compressed size, it cannot satisfy the main function of an observatory to see to great heights; it thus strays away from being an observatory. Campfire (2005) departs from our image of burning red flames and appears as a bonfire made of dark blue. Chung’s dealings with form may seem like an extension of traditional sculpture; nonetheless, her work breaks away from of the domain of traditional sculpture in which one represents existing things through artistic skill, as is the case with ordinary traditional sculptures or objets. Her works accomplish this by exposing a new directivity while oddly and continuously confusing the ordinary system of thought possessed by people who have adapted to the structural function of language.

“(For Mallarmé) the word ‘flower’ names and establishes one concept, the concept of the flower. But here the concept of the flower is not the representation of the flower that appeared again to the consciousness. The concept of the flower does not bring attention to the concrete flowers we see, and is not the ordinary symbol of the consciousness required in order to be able to think about–in order to understand, in order to be able to grant meaning to—the flower in general. The concept of the flower does not substitute the ordinary flower, it is rather ‘something different from all known flowers;’ as the ‘absence’ of all flowers it is the condensation (existence) of all flowers itself. In other words, it is not a symbol that designates all flowers and reappears in similar form; it is rather the dynamic, verbal revelation of the flower itself that makes all flowers ‘nearly disappear in trembling.’”3

Even as the artist uses universally recognizable words to suggest objects, she dispels the objects’ universal conditions that the words designate. By way of words and objects that we are accustomed to she drives us outside of language and makes us aware the substance of speech. Chung’s objects shine from the base of this kind of epistemological language and, like the language of poets such as Mallarmé, do not describe objects before one’s eyes but operate as a special visual language that stimulates the concept. For the poet Mallarmé the idea was related to “the movement of language denoting the invisible, un-representable point of contact between objects and humans.”4 He has also said, “Paint not the object, but the effect that it produces… the line of poetry in such a case should be composed not of words, but of intentions, and all the words should fade away before the sensation.”5 Maurice Blanchot described Mallarmé’s poetic language in his own book through the idea of “the essential word [in the space of literature].” The essential word is a word that is not directed towards a certain goal, a word that is not fixed in the fame of meaning, an unexplained and untaught word; it is a word that by itself shows itself and is heard as a clearly articulated word. It is thus “the concentration of ambiguity,”6 a word that becomes “luminous evidence,”7 a word that urges one on with its own secrecy. We come to ponder the objects in themselves as we circle around the effects cast by the objects that appear in Chung’s works, their formal decisions, and the images towards which they aim. This is our work that we must carry out on the artist’s work. This is Blanchot’s space of literature; it is the space of art.

Objects, Words, and Sounds that Reveal the Surface of the Street

“…Language… [omitted]…is not confined to the action of granting meaning and making things familiar or understandable. It speaks of existence, external existence, and the intense presence of objects and represents not the object but the time of the event of the object’s appearance.”8

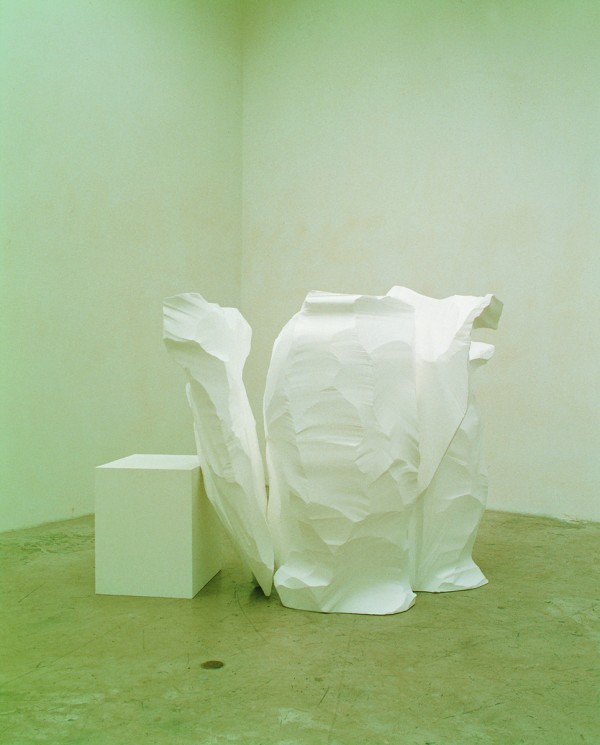

Chung’s Flower appears in the exhibition hall as a Styrofoam object 210 centimeters tall, 300 centimeters wide, and 250 centimeters deep. This sculpture, larger than a tall person, makes one sense its volume and bulk but, since it is made of white Styrofoam, appears empty or seems to lack the weight that corresponds to its bulk. Though it is an object cut to the artist’s discretion, it in some ways also resembles strange fireworks. It hardly brings to mind the typical image or figure of a flower as a “small, pretty, and delicate” thing full of love and lyrical meaning. The artist said this work “is something that turns around and goes away if I touch the front of my face and pronounce, clearly and loudly, ‘flower,’”9 and has referenced the fact that it comes from the signs for flower shops commonly seen in the street. If one thinks of these signs familiar in Korean society, this sullen and indifferent jagged, roughly severed mass seems extremely appropriate for the name “flower.” The empty signifiers of these vulgar, Korean-style functionalist signs—with “Flower” written prominently to catch one’s eye—strongly imply a certain aspect of some superficial property of our violently overcrowded compressed-growth society. As previously mentioned, it is clear that the artist’s work is not easily caught up in the artwork’s external system of discourse or mechanisms for creating meaning. However this special flower—which pushes aside the common notion of “flower” and occupies this position—may seem like an unnatural choice to us, but clearly for the artist it is the revelation of the experience of confronting the term “flower” in a social space and thus the work’s shape is extremely plausible. That is, what fills this work is a revelation concealed by the concept of “flower” that we treat as universal. It is the artist’s insight about the very concrete skin of the urban space of society.

Like the example of Flower (1999), the Lookout (1999), Gatehouse (2000), Oasis (1999) and other objects that appeared in Chung’s work in the early 2000s one could say integrate the appearance of objects existing in the streets and urban environment of Seoul. The Lookout, Gatehouse and Oasis that appeared in exhibitions resemble dull architectural structures whose humble appearance was only made for basic functions. For those born and bred in South Korean society these are ordinary objects we have grown used to, and as one looks at and dwells on the objects, we can say they are examples of strange, particular structures in our society. Though these things are harder to find due to the gentrification of the city center, if one goes to slightly less developed areas one notices the special nuances of uniformly-constructed modern Korean buildings, like the typical forms of security offices in apartments. These things appear to have a deep relationship to the aesthetic choices of the artist at this time. The artist quotes the shapes of these objects—which already exist commonly and close to us—and makes them into ambiguously-sized models or removes their unnecessary elements. In this way she estranges conventional objects, twists and removes the familiarity from inside the familiar thing, and makes the properties of the matter captured in her eye appear without any superfluities. Here the hollowness of objects is replaced with the sense of sovereignty of an artist who raises questions by re-confronting the appearance of objects.

If the exhibition Lookout (2000) took the theme of the surface of “streets” as public space of the early 2000s and brought it back to a sculptural language, we can say that the sound installation Untitled exhibited in 2012 at Culture Station Seoul 284 splits this theme of the surface of today’s “streets” into speech and sound. The artist arranged a performance in which two musicians described the scenery and sights they noticed as they walked through particular neighborhoods and streets; she recorded their words and installed it as a sound piece. When an ordinary person sees something many concrete details come into their vision. For example, when one sees a parked car one does not only sense what kind of car it is, but in a brief instant many details—the car’s color, shape, the position in which it stopped, the state of its separate parts—such as their wear or scratches—come into one’s vision very accurately regardless of one’s intention. But if we try to explain these things to someone, deciding which part to explain first depends on each person’s decision and, no matter how long we speak, we cannot make the listener perceive the thing in a way that equates what we saw with only one look. That is, the concrete reality of the thing in our vision ultimately can only be approximated through the connections forged by speech; one cannot absolutely deliver what one sees. In the end, the words regarding the objects—rather than securing the concreteness of the object through the meanings of words—appear through an experience of complexity based on the speaker’s words’ rhyme, rhythm, pauses, speed, tone, and rise and fall of timbre.

In this piece, the performers—in the short time in which they moved through the street—had to choose a number of words and read the situation or objects they saw. This activity of reading the surface of the streets, rather than coming to its conclusion with the act of describing without break, consisted of the hesitations of speech, the breaks and silence between words, incomplete word choices and their connections. Because of this, the space being represented can at first feel very vague. But ultimately, in listening the voice and the ambient sound in the work, the concreteness of vision is substituted with the concreteness of sound, that is, the collisions of speech, the relationships between the appearance of words, and their manner or rhythm. That is, the empty surface of those streets is filled with the “the dynamic, verbal revelation[s]” of the sounds of speech; the street, rather than being described through the new texture of the sound of words, comes to us through an even more concrete synaesthetic experience. Through this the surface of the street—or, the emptiness of the word “street” understood within a social system—may be unfamiliar but, due to the “subjective and creative” potential of the words operating in the artist’s domain, is transfigured anew into a specific space and filled with the elements of an exciting synaesthetic experience. Could this be something that is possible in the space of art? Chung understands very well this potential of art, and is an artist who amplifies this quality to its largest extent. This is again possible because she clearly understands the boundaries of speech and the methods for exceeding those boundaries.

The Radical Experience of Space: Gesture, Theatricality, Performativity

Looking back to the 90s, when the artist began working, it is clear that she was neither a part of Korean mainstream sculpture nor the trend of installation that had then newly emerged in the fuss of the media. She was far from the tradition of sculptural practice realized through the properties of materials or the kind of figurative sculpture based on illustrating an object and granting it symbolic meaning; but she was also not a part of the new trend of “installation art” that had spread like a fad and seen a meteoric rise as a new genre. She also cannot be grouped among artists such as Lee Bul and Choi Jeonghwa whose installations, though all using industrial materials, presented the phenomena of consumerism and the symptoms of the post-industrial society of the 1990s in terms of the subversiveness of subculture. Chung’s works—which did not illustrate images through form or grant an icon’s symbolic meaning, and which were not massively produced in a single signature style to distinguish the artist—are rebellious in that they veer away from and reject all stable paths. For quite a long time Chung’s works were only considered difficult, and Chung’s position among the various phenomena in the world of sculpture at this time was always adrift. However, in inverse proportion to this situation, she was above all not only extremely contemporary but also political, and is an artist who consistently and without fail practices a language thoroughly of the present.

Even if one reflects on the installation art after the 90s, we can say that in most cases it does not exceed a one-dimensional approach that consisted of treating the space like drawing paper on whose surface artists should compose or decorate. On the other hand, for Chung space is tenaciously choreographic space in which she takes into consideration the flow and movements of the viewers, the spaces between works of art, the duration of movements and pauses, and the resulting tension. Here, the term “choreographic” does not describe representational or expressive motions. It describes the act of securing certain situationality in space through the gestures of the sculptures and objets, the locations of the individual works and the distances between them, and the tense relationships between sculptural bodies and space. In particular, the artist goes through an elaborate process of installation that involves moving the works just one or two centimeters in the exhibition space and closely perceiving all of the diminutive elements within a space. This process turns the space into an antagonism between unfamiliar objects and sometimes elicits anxiety from the viewer through its strict and challenging attitude. This is, of course, something perfected by the delicate intuition of an artist who understands the different shadows cast by objects based on the circumstances or situationality they create.

The viewer of Chung’s works must perceive the tension of the invisible (hard to represent) relationships amongst objects and between objects and people, and by means of that tension must struggle with the abstractness of the works’ language. The sculptures’ gestures and manners of speaking differ based on their locations in space; this method of activation is directly connected to the artist’s sculptural attitude. One can consider Minimalist sculpture the first moment when the elements of space became important for positioning an objet, but despite that, even afterwards it was common for works of art to treat space as a thing disposed and awaiting decoration like a piece of paper. Sculptures that are unpacked meaninglessly and ornament space cannot be deal with their own questions autonomously. Art is even more perfected when it frees itself through securing an independent position for its own questions; through this it realizes its own politics.

Chung’s works show their strength even moreso in the white cube of the art museum. This is because, within that grid-space, Chung’s works become resistant beings that form powerfully antagonistic relationships with space as they twist or challenge the grid’s syntax. Again, the exhibition Lookout (2000) can be said to provide the best example of this. Additionally, the solo exhibitions at the Portikus, Frankfurt (2005), Atelier Hermes, Seoul (2007), and others that followed continued in this pursuit. Within the white cube the artist tended to even more stubbornly burrow into space and very minutely dealt with the space and relationships between artworks to evoke uncomfortable, alienated situations and tension. Particularly, the works do not at all appear as mild or domesticated within the sterile, white space. They are silently provocative things. Overall, Chung’s works made up of raw industrial materials and consumer goods overpower the space and exhibit a strong presence through their own linguistic mobility even moreso than works that present overwhelming spectacles or use high-end finishing products. This is precisely because Chung’s sculptures challenge, face-to-face, the myth of meaning constructed by the modernist world and the stabilization of meaning sought by a structuralist worldview.

Considering the importance of linguistic cognition for Chung, the first half of her works are weighted by coolheaded-ness, rigor and severity. However, the artist does not forget humor and wit. In the lengthily-titled exhibition at Atelier Hermes, On top of the table, please use ordinary nails with a small head. Do not use screws (2007), not only do we see Chung’s sculptural strength despite the limitations of space—we also see her wit. The exhibition hall at this time was not a standard white cube but was an example of typical postmodern architecture, its outer walls made entirely of glass. Due to the amount of sunlight coming in through the glass walls, the artist could not steadily maintain the atmosphere in the exhibition hall; the space had the problem of influencing the nuances of her sculpture with outside factors. The objects that appeared in this condition emitted light. But—with the exception of the flashlight, which directly emitted light—this was not the original purpose or primary function of the objects like the ice cream freezer, cake refrigerator, or bicycle. These were objects with apparatuses that emitted light incidentally; as the sunlight that poured into the space waned at the end of the evening, the light emitted by these objects truly came to shine forth.

On the other hand, the spatial relationships posed in the exhibition Apple vs. Banana (2011) are not a contention with white, modernist space (a false space that appears real) but appear as a game played with abandoned artificiality. This exhibition, hosted by the Kim Kim Gallery, was held in an abandoned model house from the early 90s in the basement of the Hyundai Cultural Center in the middle of downtown Seoul. The artist transformed preexisting kitchen furniture to create new sculptures, cut away from or altered the wallpaper and tile to reveal the space’s inner materials, and played on the themes of the shoddy artificiality of a particular period’s trendy (as dictated by style) interior. In the abandoned, artificial space of a model house, a table, cornerstone, aquarium, sink, carpet, and snowball sound like ordinary objects but were imported in this exhibition as the special objets of an artist whose methods are far from ordinary. In the exhibition hall, works of art—completed through a combination of the artificially-detained empty meaning of everydayness and the artist’s understanding of quotidianness—confront one another. Apple vs. Banana (2011) is the space for the showdown between these works. But this showdown is not a grave, serious fight; it is a joke made based on one’s perception of the pretentiousness and vacuousness of the everyday. It is like a witty performance that elicits our awareness of the impossibility of saying that one has experienced the quotidian life, which is full of such falseness.

Performative Sculpture vs. Sculptural Performance

Whether serious or humorous, Chung’s theatricality must be viewed through the core of its process or pretense, non-representational dimensions, and the politics of gesture and its staging of tight contention. For Chung, a sculptural objet is a subject that, like an actor or dancer on stage, must perform to meet the artist’s directions accomplished in her self-reflective linguistic cognition. This objet’s performance is also far from the kind of physical movement, acting out the expression of emotions, or representations that deliver a symbolic story that postulates the interpretation of a certain subject.

There is naturally no movement in a sculptural work. However, there are locutionary acts through sculptural forms and attitudes, and therefore, the performative language of these acts. The concept of performativity—which originally came from speech act theory—as a word may seem like it is related to performance but is in fact a concept that appears in language theory, not ordinarily performance. The philosopher of language J.L. Austin distinguishes between the constative utterance and performative utterance. The constative utterance is a way of describing a certain situation or expressing the truth of a fact, as in the sentences “this cookie is sweet and tasty” or “I have a pain in my tooth.” In contrast to the constative utterance, the performative utterance is itself the realization of an act or an utterance in which an act is latent, as in the phrases “I’m sorry” and “thank you.” Thus, the phrase “I will marry you” does not testify to the truth of a fact but is phrase that educes that action; precisely this kind of speech has a performative quality. Austin’s theory of performativity further subdivides performativity into three types: the performativity of locutionary, illocutionary, and perlocutionary acts of speech. In particular, the second kind of performativity, the illocutionary utterance, is a way of illocution through action, such as gesturing for one to pass the salt from the other side of the table; the third kind describes the level of performativity in which the result of the utterance influences one’s emotions, thoughts, or actions.10 The second and third kind of speech acts let us get a glimpse of the performative potential of art, which does not just work with the language of speech but in particular drives forth visual language. Even if we limit ourselves to speech, its performative quality confirms that speech is not simply a tool for representation but can also act as a tool for creating acts and situations and inducing new actions and perceptions. It carries, therefore creative and dynamic politics in that it speaks to move one’s heart and accompanies or implies an action.

Chung’s works do not depict some object or any image in reality. They realize, in her idiosyncratic formality, the essentiality of objects cast onto objects and the epistemological time we spend with objects. This is Chung’s sculptural performativity, the “act that doesn’t act.” As mentioned above, because the concept of performativity is not based on performance, there is no reason other than the similarity of the words for performance—which most easily utilizes the word “performative”—to monopolize this term. In this respect, there are in fact some doubts about the artist’s growing number of performance pieces. The artist continues to actively attempt to transfer the performativity, situationality, and theatricality of her object installations and drawings into the conventions of performance, but this is not only distinct from securing linguistic performativity within her work; entering into the genre of performance has nothing to do with experimentality or radicalness.

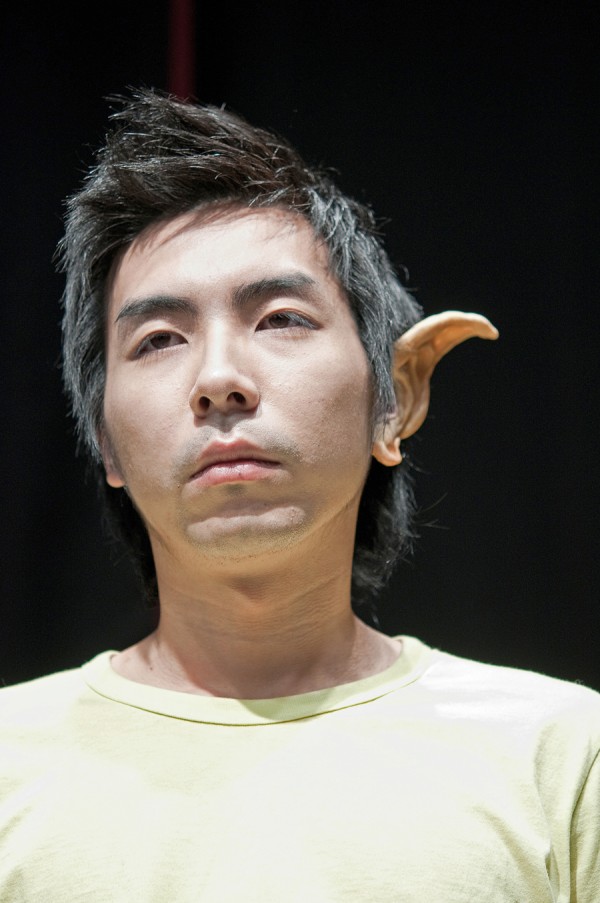

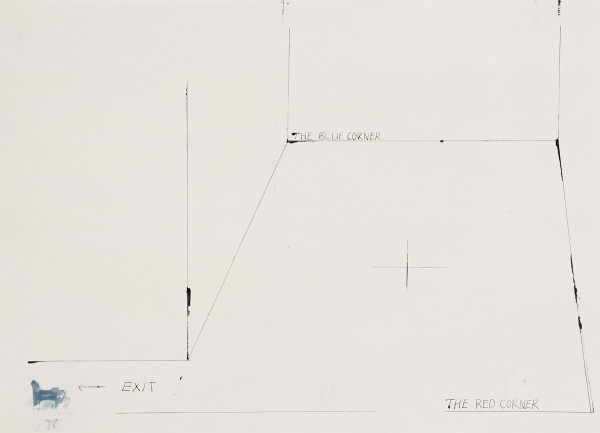

The beginning of this change came with the work, The Adventure of Mr. Kim and Mr. Lee (2010). This work, which occupied the theater of the LIG Art Hall, regarded the theater as if it were an exhibition hall. The piece developed a part of the drawing series Monster Map, 15 Minutes (2008)—first presented at the 2008 Gwangju Biennale—into an independent work. It seems plausible at first glance that this work identified and realized the potential for performance through the temporal and spatial elements it captured. However, most were concerned that the reduction of the movement latent poetically in the stillness of drawing and sculpture into the liveliness of the genre of performance—or the transfer of a work’s innate performative theatricality onto a theater stage—could quickly become tautological.

In this work, the audience passed from the dressing room—where some unusual characters appeared—to the stage and went out into the seats, directly moving around the space out to the outside of the theater. However, it was questionable when the artist attempted to make people appear as sculptures and dress them up to appear odd. It was clear that the performers—who, through their outfits and makeup, seemed like characters from fantasy—bestowed the space with the qualities and effects of the theater, itself a space severed from the everyday and that officially allows unreality. But the youth with the goblin ears, the middle-aged woman with facial hair, the boy spinning the pen, and the burly man with the long, red hair all easily fell into the trap of stories imagined between fantasy and reality. These people were not professional actors and were chosen from ordinary people, and the artist says she investigated and utilized each performer’s inner inclinations outer qualities over the time accumulated in the performance. The reason she chose ordinary people was in order to eliminate the standards and theatrical genre acting internalized by actors over the course of a long training. However, from a certain perspective, this choice clearly revealed a limitation as these figures were not just sitting still without a script but were also dressed up theatrically. In particular, though the dress applied to the characters of course revealed their sculptural texture, with it having discounted the typicality of theatrical dress already in common use in theaters there was clearly some difficulty in accepting it as merely sculptural texture. Nonetheless, there were still intriguing elements in the exposure of space and how it was circulated, the arrangement and immobility of the characters—in the respect that it continued a time that created tension—and the theatricality that did not play.

In fact, the exhibitions The Adventure of Mr. Kim and Mr. Lee (2010) and Apple vs. Banana (2011), rather than recognizing the properties of their spaces and challenging them or maximizing their antagonism, can be considered a way of wittily possessing the space while turning the space of the exhibition or play itself into a work of art. The artist actively operated on the non-everydayness innately a part of the space, and in the latter case, adopted the real-seeming fake aspects that imitated the spaces of everyday life while filling the space with plentiful sculptural details. The two pieces from the Korean pavilion of the 2003 Venice Biennale, whose space had to be re-worked due to the limitations of its architecture, A New Life (2003) and A New Pillar (2003) are some of the earlier works that already give a glimpse of her latter approach. Additionally, the recent works of art in the space of the Jeonggwanheon of the Deoksu Palace branch of the National Museum of Contemporary Art are also a continuation of the artist’s application of the pre-existing conditions and circumstances of the space itself.

The Jeonggwanheon, a building created as a banquet hall for Emperor Gojong around 1900, is not only a strange space with crude decorative details from a mixture of several cultures and periods; it is a place whose spatial personality and sense of existence itself is obscure. Not only is it remotely located within the palace; it is a marginal space with a weak presence amongst older buildings. The fake antique furniture placed in the Jeonggwanheon to make it look like a banquet hall was its only strength that could allow one to contemplate the outside scenery. The artist thus first attempted to rearrange the furniture. In order to draw the outside scenery into the inside the artist also inserted a large mirror between the furniture and thus completed the sculptural installation Inwardly, Determine Yourself (2012). Arsène Lupin, Gentleman Burglar (2012), a performance inspired by the overlapping scenery of the old palace and the downtown visible from the Jeonggwanheon, combined the sound of an actress’s voice (reading the script of Lupin) as it rang off of the rain pipes on the outer rear wall of the Jeonggwanheon with musician Hankil Ryu’s improvised mechanical noise performance. In this performance, the texture of the speech’s emotion was conveyed as its content disappeared and the mechanical noise absorbed other speech. In the performance sound was not an element that represented an image through rhythm and meter, it was the sound of a material dimension. It appeared as a sound that prevents one from apprehending what the performer talks about. Paradoxically, this noise reveals our compulsion to grasp meaning as it is, and resonates with the truth of our anxiety.

Chung’s mainstays are a performative, subversive awareness through a focused sculptural language and the phenomenological abundance of the world of objects. But as her performance productions positively lighten the political weight of the realm of sculpture, we can see that they bring another promising transformation in some respects. Chung’s language, which reconfirmed the radicalness of sculpture that seemed to no longer be possible, is now extending into performance. The recent sound performance pieces in particular are realizing a new potential of sound in terms of performative language. The materiality of sound itself not only grants freedom to the inner pressure of a listener trying to conjure an image; it presents an excitement that realizes the artist’s aesthetic idiosyncrasies through accommodating the artist’s sculptural articulation into the parts, rhythm, and texture of sound.

The Form of Discretion

The work The Time is Now (2012), recently shown in Gallery Hyundai, was an objet composed of two steel desks raised on wooden supports with a sheet of glass placed on top. This almost precarious-looking combination, perhaps because its balance is meticulously coordinated with the large and small wooden sculptures mounted between the three layers of material and the boards placed in it, looks strangely peaceful. The volumes and locations of the wooden sculptures vary based on the condition of the floor of the installation space; in this way, the manifestation of these small wooden sculptures is also the manifestation of the environment raised by the objet. It also shows a case in which is it impossible to obtain absolute horizontality. Depending on a level, the artist can only approximate as she places and adjusts the wooden sculptures one by one. Though we primarily see the stability of the combination and form of materials in this sculpture, in the end what appears is the pursuit of horizontality—that is, the absence of horizontality in the present moment. We also come to face the temporality of the wooden sculptures’ placement and, through that, the balance intended to be maintained and the tension directed towards that balance. On one hand, this time directed towards balance is also the continuation of deliberateness. Though the four sides of the steel desk demand balance in four directions, the time of placing the pieces of wood among endlessly imperceptible differences is ultimately a time arrived at though the artist’s discretion about a certain imperceptibleness.

The drawing series, Monster Map, 15 Minutes (2008), unlike the sleek lines of Chung’s earlier carbon paper drawings of the early 2000s, shows the aberrant and uncontrolled spreading of ink. This effect is actually produced by the artist, whose fingers on both hands are paralyzed, drawing with a ruler; the lines’ movements, stops, advancement and anxiety are the revelation of the other-body nested in the artist’s body and reveals the private present of the artist who at that time relates to that body. Jean-Luc Nancy has said, “the painter reproduces the discretion of presence.”11 Realizing the result of a work of art is the free judgment and assessment of the artist who decides when to move and stop her hand and when to advance; it is the private time within this process. Discretion means both free judgment and deliberateness. The concept of free judgment implies that one can decide based on one’s own free will, but it also implies that one makes assessments in order to decide freely and act; it already connotes deliberation and thoughtfulness. If we view the work as an extension of this free judgment, it is fair to say that it exists for all artists. However, this discretion through thoughtfulness is intensively involved in Chung’s work. When the artist’s actions dealing with form are an extension of the artist’s self-reflective assessment, it makes us realize that art can become possible through art. In particular, for Maurice Blanchot, discretion cannot be simply limited to the consideration or politeness based on social manners. For him, discretion allowed for literature to be literature:

“Discretion – reserve – is the place of literature. The shortest path from one point to another is literarily the diagonal or the asymptotic. He who speaks directly does not speak or speaks deceptively, thus consequently without any other direction than the loss of all directness. The correct relationship to the world is the detour, and this detour is correct only if it maintains itself, in its deviation and distance, as the pure movement of its turning away.”12

As we have seen in Chung’s works, we cannot grasp a direct key, background, or definite meaning related to the work. The artist only reveals her thoughts through forms and the relationships between materials and individual elements. For the artist this is also not a world that can be expressed or explained by connecting a few phrases. The forms that result in the works in the end do not damage some world of the artist and are the traces of her deliberation over a process of approximation. Even while moving and acting, the artist’s time follows a path of stringent assessment as she detours around being able to easily touch upon some value or meaning and falls into silence. The work is precisely the remnant and revelation of this sort of self-reflective time. That is, the vagueness that appears in Chung’s work is not just indefiniteness, it is the concentration of form that results from this focus and decision; this concentration of form is a denotation of the time made by rigorous discretion.

When the artist makes a work (and perhaps when we speak about a work, too) the work’s complexity disappears as we choose the most direct way of showing its meaning. The work of art, regretfully, cannot speak for itself; it is not a sovereign object. In this respect the work of art only comes to exist through the artist as an object, or through the speech of those talking about the work of art, such as this author and the audience. Ultimately how one produces of a work of art through speech and the bodies of objects is a continuation of discretion. In order to make the space of art exposed, the artist’s discretion—sometimes silent and distant, sometimes acting—is linked to the ethical practice of art in which one recognizes the inevitable otherness of the work.

Chung’s works do not subordinate objects to the meaning of words but instead return to the objects themselves; they enervate the given meanings of words from the boundaries of the world. They find the center in a world of inertia. This center is a world of the other in which meaning is unstable, a rebellious world; this is where Chung’s radicalness emerges. Art is not merely a political or philosophical thing; it carries its own politics that can examine politics and philosophy on its own. Chung has come to accomplish a deep aesthetic world by practicing a thorough discretion that allows her varied works to produce artistic events possessed of their own politics. The restoration of pure relationships with objects, the appearance of signifiers of signifiers that allow one to encounter hidden phenomena, insight that emancipates one from one-line interpretations of words and objects, the experience of language and things existing with “the other of all worlds.”13 Here, finally, lies Chung’s concentration of ambiguity, her luminous evidence.

-

The Jeonggwanheon is a pavilion used for the King’s relaxation in Deoksu Place. ↩

-

Chankyong Park, “Lookout: The Objects of Chung Seoyoung,” catalogue of the exhibition Lookout, Artsonje Center, Seoul, 2000. ↩

-

Joonsang Park, On the Outside: The Literature and Philosophy of Maurice Blanchot, Ingansarang Publishing, Seoul, 2006, pp. 163-164 ↩

-

Ibid., p. 170 ↩

-

Ibid., p. 169, a letter from Mallarmé to Henri Cazalis, October 30 1864, originally in Stéphane Mallarmé, Correspondence, 11 volumes, edited by Henri Mondor, Jean-Pierre Richard, and Lloyd James Austin, Gallimard, Paris, 1959-1985.- ↩

-

Maurice Blanchot and Ann Smock, The Space of Literature. University of Nebraska Press, 1989, p. 44 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Joonsang Park, Ibid., p. 166 ↩

-

Chankyong Park. Ibid., The original text was taken from Chung Seoyoung’s contribution to Modern Literature. ↩

-

Bohyeon Kim, Introduction to Derrida, Munye Publishing Company, Seoul, 2001, p. 88 ↩

-

Jean-Luc Nancy, The Birth to Presence, Stanford University Press, California, 1993, p.348 ↩

-

Maurice Blanchot, Friendship, Stanford University Press, California, 1997, p.171 ↩

-

Maurice Blanchot and Ann Smock, The Space of Literature, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 1989, p.228 ↩