Lookout: Chung Seo-young’s Objects

These objects would no longer be a reflection of vague, inexpressible feelings in the principal character, nor would they be an image of his anguish or a shadow of his desire. To be precise, if these objects were still to be used momentarily as the props of man’s passion, they would only be temporary. And they would accept only superficially the oppression of various meanings - for instance, mockery - in order to better demonstrate just how much they can remain strangers to man. - Alain Robbe-Grillet

Objects

The double image in A Sculpture with a Good View and a Bad View suggests that familiar things can easily become unfamiliar or else shift their meaning. In fact, most of Chung Seo-young’s works are simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar, but a function of her work that creates this and other effects shocks in a different way than in the modern methodologies of artistic venture. Rather than encouraging perceptual specificity that secures purity of experience, breakdowns that assure critical distance, and shocks that reveal the lazy habits of consciousness, Chung’s works may give the subtle trauma that “throw away” the spectator into a post-psychological space of muffled shocks.

Her works are familiar to us because she creates them by referencing and modifying the body and the functions of objects such as furniture. Her works emulate the functions of objects that could be the core of any artifacts, than the objects themselves or their intimate relationship with the body. And apart from the objects’ functions—linoleum as floor covering, lookout as panoramic viewpoint, flowers as decoration—her works don’t mimic much else. The objects she copies are “function-identical,” that is, their functions are indistinguishable from the objects themselves, like a soldier’s mess kit. This idea is expressed in Sculpture with Rubber Band, where handles made of rubber bands hold the sculpture in its hanging position; or in things like the dial of an old rotary telephone or a bicycle wheel, objects that have long lost their novelty for us. This is the familiar side of Chung’s work.

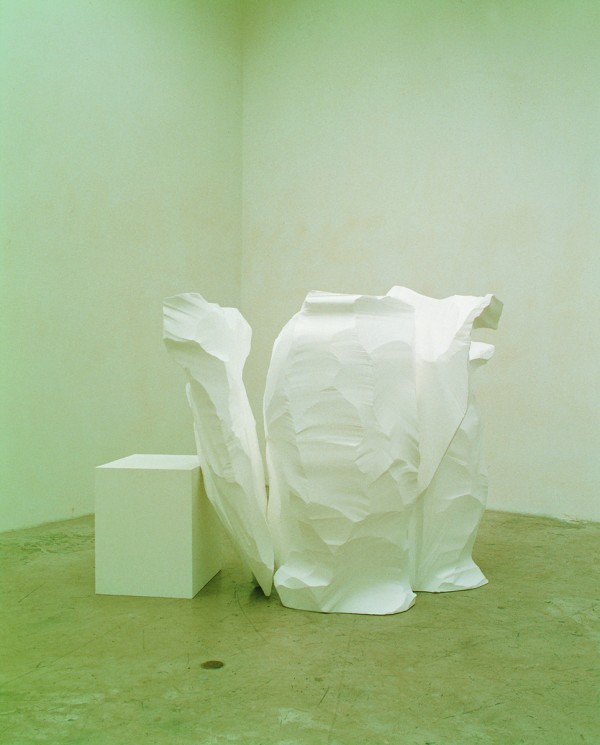

Objects in a space, sometimes askew, sometimes lying flat, sometimes leaning, struggle against us, for in the interval between the object and the space surrounding it, other objects can finally express themselves fully. In this way, we rediscover the obliqueness of space, which is the furthest removed in The Sculpted Bride and Vase with Road, and which constitutes the unfamiliar in the artist’s work. The unfamiliar in her recent works is composed of more complicated mechanisms such as the rearrangement of a work’s proportional dimensions, the subversion of inside and outside, and the eye’s uneasy gaze over it all. For instance, Lookout oscillates ambiguously between the life size and the miniature. What is normally seen on the inside, as in Flower, is seen on the outside, and what is normally seen on the outside, as in Lookout, is seen on the inside. These result in the indecisive presentation of a specific temporal space enclosing isolated, helpless objects that we see from inside their structures.

But this dialectic between the familiar and the unfamiliar still doesn’t lead us to the thrill of the new. If her objects are surprising, like discovering a long lost friend, it is because of the situation in which the surprise that we anticipate does not occur. And this is because of our usual easy acceptance of this no startling result, which is the fruit of that interesting phenomenon, may be the famous capitalistic sentiment of boredom. For instance, in -Awe the symbolism and aestheticism of the object—in this case its character—is on the contrary an apparatus that moves toward neither an extraordinary situation nor a noble condition that would go beyond the ordinariness of the creative method or the material. They go down rather than up on high, meaning that on first glance the artist’s works seem aesthetically elegant, while at the same time advancing their right, or what could be called their morality as objects, ethics of facts.

It’s also possible to explain this idea by listing the basic materials that Chung has been using: 1) magic marker; 2) wood; 3) carpet; 4) styrofoam; 5) cement; 6) linoleum; 7) glass; 8)

sponge; 9) sheet metal.

The works that are composed of these materials don’t see to follow any of the general tendencies of sculpture to naturalize or humanize their characters by crafting them. They seem to be free from the value of a given use, as if they were exhibits at an industrial education fair demonstrating the relative importance of each material. Thanks to the artist, styrofoam is “naked”, revealed as a license of it’s own materiality. Moreover, while most of the materials are common in the world of interior design and are hardly liable to attract our attention, they are the stars of the artist’s works and purveyors of traumatic experience and continual strangeness. The artist has chosen them for their un-remarkability, and frequently uses them in her works to emphasize nothing more than their roles as necessary functions of their own structures. Lookout exemplifies this idea.

And whereas not all of Chung’s works function like this, those that do resemble pieces of furniture—except that by psychologically and materially owning furniture, an owner bestows on it a value and a history. And it is a question of furniture, of modern furniture that one can walk up to without being shy, and still maintain a certain distance with its retrospective density, its sentimental value, or its authority and detail as specific objects most of which have been won over to the practical activities of man. Of course, the artist doesn’t reveal her works smack-dab, as though they were Kim’s Club merchandise. Sometimes her works are like functional, concentrated objects that economize on artistic energy and technique, sometimes they seem to be profound allegories, and still other times they seem to guide us toward a “forest of symbols” as Breton once put. From a wealth of the ordinary is born a unique paradox, nothing less than that the same ordinariness is suddenly “something.” But her works turn a cold shoulder to the spectator’s desire for meaning; when the spectator is in front of her objects for the first time, she realizes that she will get no response.

If Lookout isn’t that which resembles a lookout, what is it then? To skip to the conclusion, the problem is not what is the lookout, but why the lookout, why “that”. The pact already concluded between work and spectator, the loss of necessity would be the real meaning of the object, and if not “meaning”, the “rising” of the object. So when I amble around the art space asking snide calculations about how many times I should ask myself the same question about and give myself the same vain response to a work’s “meaning,” I would do well, before the meaning comes to me, to check my answer in the coatroom. In other words, like in the charm of the crime scene, truth revealed kills the mystery and curiosity toward of missing objects, and as long as they keep their secret they keep their meaning as objects. Like a detective narratives, the disclosure is unimportant; what is important is the duration, the sequence as an object remains in stimulating curiosity. So this is the question: If these things are nothing more than what they are, how is it possible to view them allegorically and with a given system of meaning? Why is their meaning ambiguous? Why, when their meaning as objects is transparent, are they so opaque?

Flowers!

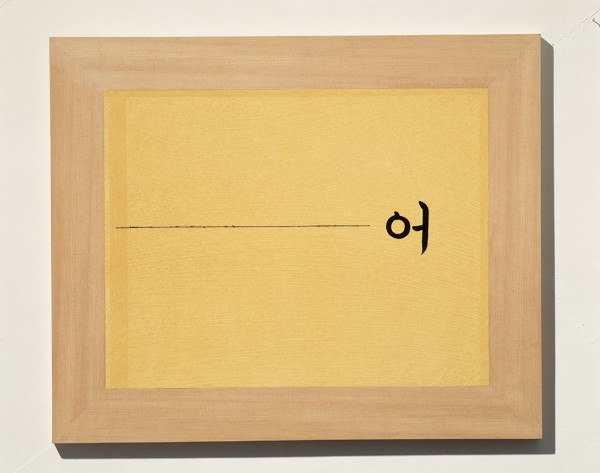

Chung expresses the atmosphere(or subjectivity) and the presentness(or objectivity) of her work through her treatment of language. From the preceding remarks, one can guess that the artist’s essential method is to objectify language by reifying it. In Flowers, what the artist imitates is not living, objective flowers, but the word “flowers.”(“kkot(in Korean)”) According to Saussure, as soon as the flower is represented by a sound and a meaning, as soon as it belongs to the abstraction of a linguistic system, it loses its living reality. Chung’s starting point is just that, the absolutely necessary imitation of language, which is the creative and subjective function of speech that seeks to avoid its own system and the death of the object’s concrete reality, which is dictated by mystery of language.

She wrote, “‘Flowers,’ one red word that fills up a small square background panel, is probably the sign you see the most often in the street. When I see this sign I get the distinct feeling someone is suddenly spitting the word ‘flowers’ in my face before turning away from me. Afterward I’m just stunned.”

Of course, the meaning of Chung’s anecdote is not that she doesn’t refer nature in general. Because her imitation, which is more like the conventional abstraction of an object such as a Chinese character, finds itself at opposite ends with language and its real communication, her action, starting at a certain epistemological point, is nothing more than an empty pantomime. The chrysanthemums and roses displayed in the shop windows in her amusing anecdote are flowers in word only. This nominalism, which dominates all her work, is precisely what continually changes the familiar into the unfamiliar, while creating an increasingly extreme duality in the objects she has imitated and the props she has staged or presented in visual leaps.

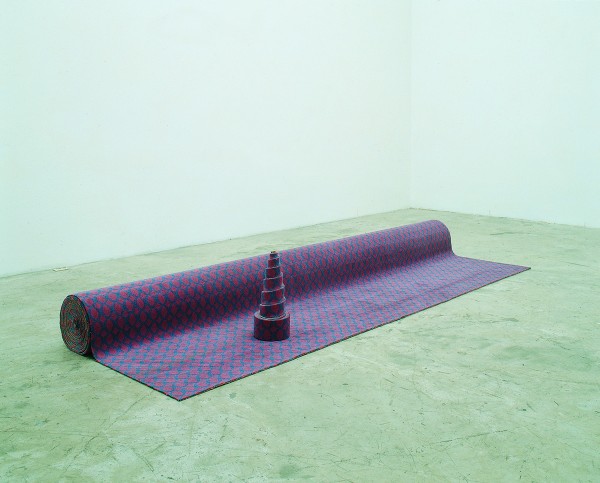

The more the stuffed rabbit head that the actor wears on stage for children’s theater or the telephone without line he puts to his ear fulfills their functions as convincing props in the play, then the more these objects called for their intrinsic strangeness. We can see how carpet in her work spreads out its massive self on the floor in its effort to be in fact a “linguistically” carpet, and how it visually gleams with all possible means, from its brilliant surface to its colorful motifs. Carpet, Lookout, Cactus and other works are all means to lost ends and inner connections, traps that contain meaning made of position, surface and form. These works don’t seek to have no meaning, they seek to be meaningless. It is as if in a warehouse of objects from which their meaning has been removed, one now walks amidst the unreal. The true worth of a riddle is in the extravagant response to it. That idea resonates more in the realm of poetry than of prose. As Sartre noted with satisfaction over 50 years ago, poetry does not even “use” language.

“Poets are who refuse to utilize language”. Rather, poetry “serves” language. “Indeed, it is meaning alone which can give words their verbal unity. Without it they are frittered away into sounds and strokes of the pen. Only, it too become natural. … but a property of each term, analogous to the expression of a face, to the little sad or gray meaning of sounds and colors. Having followed into the word, having been absorbed by its sonority or visual aspect, having been thickened and defaced, it too is a thing, uncreated and eternal. For poet, language is a structure of the external world.”

Display

If objects don’t enclose absolute meaning within themselves, then replacement for meaning would be nothing but arbitrariness arranged in space. Chung’s most recent work introduces us to the arbitrariness and the rootlessness of things, to the existential “chance meeting” with them, or to the absurd. For her, an exhibition is a kind of absurd interior design. It is definitely not satisfying design or symbolism in a well-ordered in utilitarian sense but, on the contrary, cold to the point of frigid interior design whose goal is to display things and in a way prove that interior design is impossible ultimately. Like objects, her works are too isolated from the outset to create any meaningful, harmonious system. Her works exist side by side and express themselves as silent individual parts, instead of as an organic whole.

In this sense, she understand the principle of installation, for her instead of installing works of art, to install objects is art work. Nor does she just haphazardly align works as so many artists do in bad group shows, but makes them coexist. Then she asks us why they coexist. In reality, besides a certain atmosphere, it’s futile to find among Chung’s objects a connection between a system of meaning and a subject. And besides coexistence among individual objects, the display is revealed to be kind of lie, and the connection and meaning among works become an artificial gesture. Let’s take a moment to contrast this example with one of her older works in order to see more clearly that she had steps toward recent.

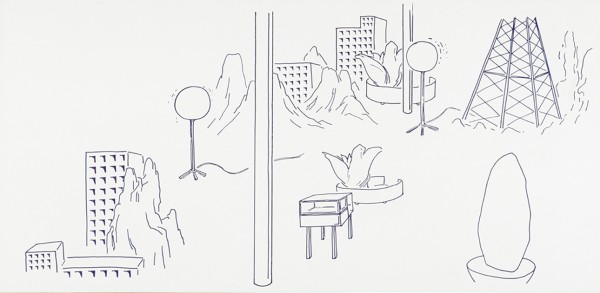

In Several-Dozen-Drawings-and-Sculptures Sculpture, Chung’s use of individual “works,” of sculptures and drawings, for example, reveals the absurd nature of interior design par excellence. The title of the work implies a domestic space in which one hangs small works, rather than a large exhibition space. Domestic and public space overlap because the artist installs works that obey norms of decorative taste more than principles that are the basis of meaningful works. What she refers is not domestic space itself, but its display, where individual works that exist independently of each other as in an exhibition space, or that are reduced to the level of little pictures or pieces of furniture (that in reality are right at home) are installed in a room that is a single, unified space. And since the rooms of our own homes function as exhibition spaces, it’s only normal that exhibition spaces function like rooms of our own homes. In fact, if we accept that the museum is without ideology, then there is no real difference between the exhibition space and the domestic space. All art works are objects in space.

From a collection of objects, the resulting display is in the end a certain atmosphere. More than Several-Dozen-Drawings-and-Sculptures Sculpture, the work Ghost, Wave, Fire that Chung created afterward at the Kumho Museum, exemplifies this idea, as go further in the other works in the Art Sonje Center. Works are all atmosphere makers, which is the common denominator of the original objects, their force and, at the same time, their ghost or fire, their veil.

Whereas a problem with atmosphere is that it creates easy myth around the “Art”, it also tells us that the world around it is ambiguous. Atmosphere is the final result when one is confronted with the relative unknowability of the object. More important than her objects’ ambiguous atmosphere is Chung’s success in investing this atmosphere in anything. But the reality of the situation is more complicated, especially because of the intense malice of the art system.

Even if the artist’s impassive objects accentuate the banality and materiality of the object, as “works” they create an atmosphere because we don’t understand what they are. Again, this is the contradiction that is specific to her work and that corresponds to the void between object and meaning. Simply put, when together, her works create an artistic aura in a way. This is because “we” don’t understand what (especially modern) art is. Of course, even though her works continually eliminate artistic codes and take precautionary measures against simple mystery, there is no way of finally knowing on what level they will go beyond mystery in the unknown space commonly known as the museum. And of course, the art system, not the artist, will regulate their role, a problem that will only arise at the moment of the questioning. Specifically, how much will her works disturb art as a institution?

The oppression of meaning

It’s time to talk more about the “veil of meaning” or the duality of atmosphere. Let’s begin with the conclusion: meaning in Chung’s work is a trap. According to Alain Robbe-Grillet, whom I quote at the beginning of this essay, Chung’s objects would seem to accept the oppression of meaning.

The world of the author of Pour un Nouveau Roman, a world that is called “subjective objectivism,” and the syntax of Chung communicate with each other, as if their objects described the objective and the neutral; but in reality, the only rule of this technique is that of a subject based on the object and the world. Here, the act of writing doesn’t mean that the subject—author or protagonist—conquers the object projected into the world or into the object, or that it uses the world as an instrument within the common order of a world vision, but that the world is to be left alone, that “an object is to be just an object and a man is to be just a man.” Through his eyes, man sees the world in all its minute details; but because his description necessarily becomes part of the unknowable, the world remains ambiguous. Ambiguity is the result of neither psychological nor logical confusion; rather, it is in and of itself truth and intelligence, above all capable of expressing changes in consciousness, time and contingency, all of which possess but temporary meaning. If the examined world seems but dry objectivity, it is because the object’s fragile identity, infinitely changing according to the weakness or fickleness of memory or contingency, is a given in our lives.

Ambiguity, which is the result of recognizable ignorance, can neither disappear nor reach the partial, yet still difficult meaning hidden behind the subject. This is because of the distance that exists between the self and the world, the ambiguity that is a carefully and actively researched answer itself—research that testifies to the absence of humanistic passion for the difference. In Untitled, which is like a conceptual diagram or map for the entire exhibition in Art Sonje Center, the artist presents the object with a simplicity that is explicit and to the point, with lines drawn with “indifference” or like dictionary drawings, but in which the organization, dimensions and “wrong” structure are all drawn “indirectly” and arbitrarily, just the way memory would choose and organize the object. In this way, Chung couples a temporary symbol or allegory to an object that is then capable of changing itself continually and consummating itself immediately, all of which constitutes the oppression of meaning; whereas the subject (the artist or the spectator) and the object, the work and the subject that evokes the work, the real and the imaginary, neither merge with nor touch one another, for they are made to ignore one another. And in this way, the object stays within the object. A bottle and a cap that doesn’t go with it remain strangers and grow distant not only to one another, but to us.

This method safeguards the modern experience and, above all, the reality and the vanity of daily life. The imagination that creates a rolled carpet rising up like a tower and symbolizing the suburban nightclub in all its vanity can be but temporary and capricious like a missed rendez-vous, and sure that the rolled carpet spiraling up is but a rolled carpet. This imagination is but the revelation of its fleeting uniqueness. And Camus said , “It is a virtue of weariness . Weariness comes at the end of acts of a mechanical life, but at the same time it inaugurates the impulse of consciousness.” Moreover, “the ultimate goal of the object is to block the path and send man back to himself.”

By way of conclusion

Since the ready-made, it is well known that the object in the artistic system and the object in daily life possess the value of revelation through an exchange of their different phases. But unlike the ready-made’s success, where an exchange seems impossible between these two poles, Chung’s success lies in her introduction of the art of daily life by positioning herself at an uncertain point on the line that separates life and art. Moreover, recently the ready-made is seen as the audacious science of the thoughtful mind, so it is probably necessary to remember that the materials chosen have nothing to do with auratic craft. However, instead of still supposing that this is a disclosure in art historical discourse, better to choose the path having nothing to do with the mechanism behind this change. Outside the institution(if there exists), works of art has (not contextually but) essentially equivalent value with the apartments, and kiosks in the street as a furniture of the world. To go even further, a critical look at the world is in reality no different from a critical look inside oneself, and could be an important alternative to the doubts and responsibilities of daily life.

If one takes this perspective, objects are no more dramatic “beyond” us. And if there is a drama in the exploitation of the art history’s market—for example, commercial inventions and arguments occurring in the context of autonomous values—it has not much thing to do with this work.

On the other hand, it is probably more realistic to verify the difficulty of a universal extension of a certain consciousness, represented as a heroism of scientific consciousness. In general, and maybe even specifically as the work of a woman, Chung’s art is a chance for us to reflect on the uncertainties and instabilities of the subject in Korea today. It is also a chance to reevaluate our existential “anxiety” about violence and self-defense in modern life, especially in this miserable country where not only is the reevaluation necessary, but where contemporary Korean sculpture reevaluates the place of Chung Seo-young. But that’s another story, one in which it would be easy to show how Western sculpture has evolved in Korea.

It is no exaggeration to say that in the same way that Koreans have been abandoned in the world of objects, Korean modern sculptors have been abandoned in the world of sculpture, in spite of which they have succeeded the rare feat of creating a powerful and generalized fetishism. From the wretched, sword-carrying object that towers above the Kwanghwamun intersection in Seoul, to the shoppers of the mushrooming suburban complexes, zealots pushing shopping carts up and down aisles of splendid merchandise in discount warehouses, in front of it all, how not to think about our collective and historical hunger for the object? I get the feeling that in general, Korean sculpture, in the worthy image of a country and a law that legislates a work of art in front of every big building, is the ideal example of society as phallocracy. It is here one discovers the context for Chung’s way of de-fetishizing the objects we substitute for desire. May be this is too simplistic.