Chung Seoyoung: Mind Body Ghost

The word sculpture became harder to pronounce—but not really that much harder.

– Rosalind Krauss, Sculpture in the Expanded Field

I. ENIGMOLOGY

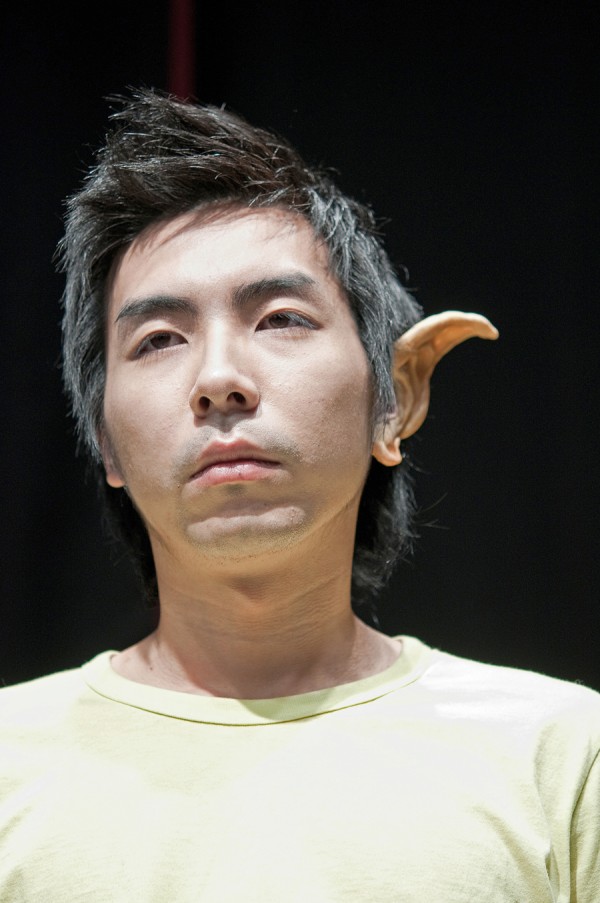

There is a modernist house on stilts, the size of a child’s bunk bed, complete with a ladder—it is a treehouse without a tree, or a miniature forest-fire station made of wood. Near it are five pieces of roughly carved styrofoam clustered together, each more than two meters in height. One of them is leaning against a white pedestal. That can’t possibly be a representation of a flower, can it? Another object in the room looks like a shipping crate, or an altar made from plywood, with a round lamp sitting on one corner. From a distance, it also looks like a tiny kiosk. There’s an ear attached to the large white expanse of a wall; it’s veiny and pointy on top, like that of a goblin’s. What is it doing there?

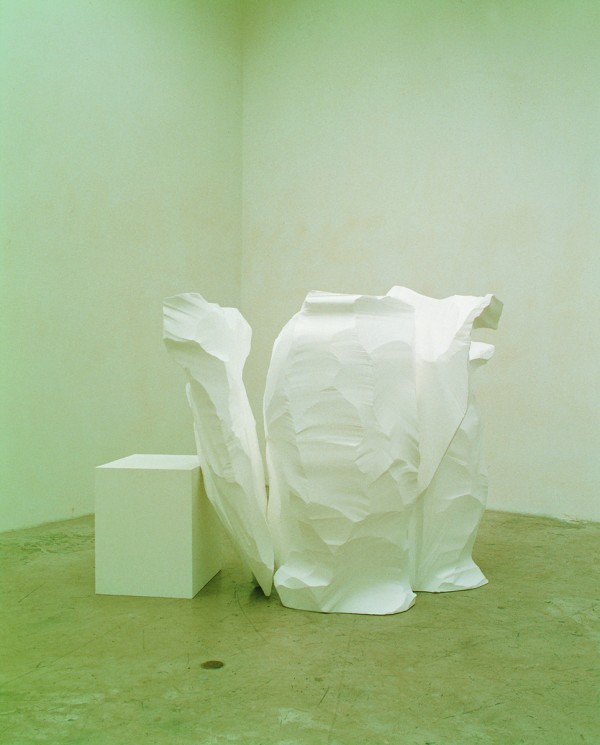

For some viewers, entering the first-floor gallery at Seoul’s Art Sonje Center in late August 2016 to see the group exhibition Connect 1: Still Acts might have been an uncanny experience. Three of Chung Seoyoung’s artworks had been shown before, 16 years earlier, in the exact same positions, in her seminal 2000 exhibition Lookout. And here they were again: the miniaturized wooden fire-station, Lookout (1999), approximated from an image on a postcard; the bulky-looking but lightweight styrofoam petals of Flower (1999); and the boxy, plywood Gatehouse (2000), a piece of shrunken vernacular architecture. The ear on the wall, titled perhaps to preempt viewers’ responses, I Don’t Know About the Ear (2016), was the sole addition to the 2016 exhibition. On rare occasions, a performer would put it on and walk around the gallery, or sit on the stairs outside, making it temporarily disappear from its spot in the exhibition space. You could almost imagine that the three older artworks had become invisible during those intervening 16 years, and then had reappeared one day, like specters disturbed by the recent renovations at Art Sonje. Yet just as they were originally, Chung’s sculptures are resolutely enigmatic—which is exactly how she wants them to be.

As one of the central figures of Seoul’s independent art scene of the 1990s and 2000s, Chung practices what could be considered the dying art of sculpture—except her objects are anti-modernist, tightly embodied paradoxes of representation, physical material and language. However self-contained they appear, they ultimately only come into existence in a viewer’s mind as one juggles the title and linguistic components with other visual, and sometimes invisible, elements. So while, since the 1960s, sculpture as a genre has ventured into “expanded fields,” negotiating relationships with the natural landscape or with architecture, as art historian Rosalind Krauss proposed—or dematerializing, as Lucy Lippard suggested, or even digitizing completely in the 21st century—for artists such as Chung, it is the potential within objects themselves that could be expanded.

Walking up or down one flight of stairs at Art Sonje Center, visitors to Still Acts were reminded of two other prominent modalities in recent art practice. Upstairs, Lee Bul had transformed the gallery space, covering the floor in cardboard boxes and assembling sound and video elements, drawings and past artworks by herself and others into an immersive environment. Downstairs, Sora Kim had left the space nearly empty except for a bookcase awaiting donations and a table where performers were stationed to interact with audiences—evoking the transactional or participatory scenarios of the “relational aesthetic” that many in the generation of Lee Bul, Sora Kim and Chung Seoyoung have tended toward. Chung’s objects, by contrast, felt almost forlorn and isolated from one another in the large, brightly lit space. They emphasized the qualities of their environment—in this case, Art Sonje’s new ceilings and lighting system—as much as the large gallery emphasized the sculptures’ own unique strangeness, and estranged-ness.

Space is one of several crucial, intangible elements in Chung’s practice, as she explained to me in a conversation we had in early March in New York on the occasion of her first solo exhibition in the United States—which she gave the humorously cumbersome title Ability vs. Invisibility—at New York’s Tina Kim Gallery. We were looking at Curb (2013), a three-meter-long piece of aluminum cast in the shape of a sidewalk’s curving edge lying on the concrete floor of the gallery, right at the entrance—a representation of something from the outside just as you have stepped inside—when Chung explained: “The choices I make when I place a sculpture are all about how it reveals the negative spaces around it. I often imagine a new aspect of a space when the sculpture is there. In this exhibition too, the placements of the works are not meant to be harmonious but are about introducing a new character to the space.” I had felt a presence behind me and caught sight of something up on the wall to the right—a white rectangle, roughly the size of A4 paper, and then even higher up, a small, amorphous, rock-like object made of aluminum. The piece, called Stone and Mark (2016), pulled my attention away from the horizontality of the gallery floor that Curb had evoked and toward the neglected corners of the ceiling. In the next room was another “invisible” presence (with its own “abilities,” nonetheless), Corner Sculpture (2011), a pile of roughly applied concrete residing at the intersection of two walls and the floor. With a strangely anthropomorphic presence, it looked like a sculpture hoping not to be noticed. Its diminutive form simultaneously drew attention to the size of the gallery.

While Chung’s works share a wry mischievousness, she also emphasized the discreteness of each within the context of an exhibition. “The idea of connecting each sculpture and putting together a specific narrative never crosses my mind,” she explained. “I don’t see individual works coming together and concluding in a theme. I like to call it more of an experience, because seeing a sculpture is a physical experience.”

As well as being self-possessed, her sculptures are also imbued with a kind of cryptic logic, and adhere to their own set of existential criteria. For instance, Chung uses materials and forms that are easily recognizable, like the wooden sculpture Table (2007), which resembles the ordinary object of its title except for a portion roughly the size of one person that has been cut out of one corner and part of the leg. As Chung said about the work: “It was important for me to leave out some aspects of an object—the leftover [parts] speak more because social memory fills the gap.” In this sense, the audience does become a participatory element to the work—but they have to realize that ability in themselves.

Chung’s works are undeniably challenging. During our discussion, I admitted to being frankly baffled by several works in Ability vs. Invisibility, including a photograph called Evidence (2014), which depicts a fist holding an odd assortment of branches and pens. She explained the piece to me: a few years ago, she’d lost partial feeling in her hands, stemming from dysaesthesia—a condition in which damage to the nervous system causes discomfort when touching something. One day, when she was rummaging through her bag looking for her keys, she grabbed a random selection of unrelated things. Chung didn’t seem offended or put off by my incomprehension, describing her works as often embodying “a very abstract concept.” She said, “I prefer the two different objects, from the everyday and social memory, to collide and make a third form: an unknown territory. The moment of realization, among the world of many unrealized things, I would describe as the ‘third form.’ I believe sculpture mediates this process of being aware.”

II. THREE-WHEELED HOUSE

Awareness is a simultaneous state of knowledge and perception, a cognitive and experiential process that is neither purely visual nor ideological. In this way, Chung’s search for a “third form” also reflects her generation of artists’ desire to overcome the rigid dichotomies and cliques of the postwar era. During the 1980s, when Chung came of age in Seoul—she received an MFA in 1989 from Seoul National University (SNU)—the art scene was roughly divided along generational and ideological lines between modernist abstraction and very overtly politicized art. “There wasn’t a lot going on in the Korean art scene in that year,” she explained to me. “It was also very insular, and as a student I was exposed to Modernism and Minjung [“people’s”] art only. I felt very suffocated and wanted to explore outside of this scene.” She and her peers started looking for their own “third” way. She moved to Germany for seven years following her MFA degree, where she studied at the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Stuttgart with a Swiss professor, Jürgen Brodwolf, whose grim sculptures recall mummified figures—perhaps prefiguring some of the gothic and figurative traces in her later works. Eventually, Chung explained, she found Europe to be too static, and that in her time away there had been big changes in South Korea, with political openings and a wave of development that came in the years after Seoul hosted the 1988 Summer Olympics.

Chung’s return to Seoul in 1996 coincided with a new wave of artist-run initiatives and an increasingly international, and conceptually oriented, art community. Chung was involved with all four of the important nonprofit spaces that opened around that time: she was an artist-resident at Ssamzie Art Space from 1998 to ’99 in its inaugural year; she was one of the founding members of Art Space Pool, and its journal Forum A, in 1999; she and sculptor Choi Jeonghwa were invited to hold the first exhibition at Alternative Space Loop the same year; and Art Sonje Center, founded in 1998, hosted Lookout in 2000.

The influence of Chung’s work was felt primarily through its difficulty and refusal to offer up experiences that were expected or pleasing. Curator Hyunjin Kim described the impact of Lookout:

It left the most intense and unfamiliar impression on the Korean art world between the beginning of the period of ‘contemporary art’ in the late ’90s until the early 2000s …The viewers … had to confront a new difficulty they had not yet experienced in previous local exhibitions. Even at that time, the pressure to read art as conveying a message was predominant among the majority of the art-viewing public. Because of this, Chung’s works in the exhibition space—which could not be grasped as symbols of a certain message or meaning—were indeed tremendously rebellious and political.

One important break that Chung and her peers made with their predecessors was to incorporate everyday materials into their work. For Two Hours, a three-artist exhibition in September 2016, also held at Tina Kim gallery, curator Hyunjin Kim proposed that Chung, along with Bahc Yiso (1957–2004) and Kim Beom, who had both returned to Seoul after periods in the United States, were among the foundational figures in establishing the 1990s art scene in Korea. Though each had a unique practice, in Hyunjin Kim’s words, “these three never simply delivered the mainstream Western styles people would consider as superior.” The ex-New Yorker Bahc Yiso is often credited with injecting poststructuralism into the Korean art scene with his very conceptual multimedia works, while Kim Beom is known for his offbeat, anti-art approach laced with dark humor. For Kim, Chung’s sculptures are notable for combining Korean-made construction materials—styrofoam, linoleum, lumber, plywood—with “the abstractness and object-hood of the words of her stimulating titles.” Unintentionally echoing the title and certain bodily forms found in Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23), for instance, The Sculpted Bride (1997) is a wooden tripod frame with a circular top, with each of its feet resting in a plaster bucket. A curtain of yellow packing foam is drawn part way around like a veil. Another work, Ghost Will Be Better (2005), is made from a roll of linoleum sitting on a 4-meter-long, 1.8-meter-wide sheet of plywood on low sawhorses. The work’s title is printed in black all-caps on its surface, and there’s a small white-plaster pile in the middle, itself vaguely resembling a ghost. The still-unrolled portion of linoleum suggests that the act of covering over—the wooden floor, traces of the past—is still in process, disturbing the ghost. Hyunjin Kim argued that the materials and approaches these three artists used signaled their sense of irony and absurdity, and a “sharply articulated awareness of authoritarian society.”

Refusal—as an attitude, and particularly of what she called the “conventional semiotic interpretation of art”—was part of Chung’s awareness. When she and Bahc Yiso were two of the artists selected for the Korea Pavilion at the 51st Venice Biennale in 2003, both went out of their way to refuse the opportunity for spectacle. Bahc Yiso made small, clumsy plasticine models of the world’s tallest buildings and a small cordon of miniature carvings of the other pavilions on thin strips of wood. Chung’s objects were similarly resistant—both to the grandeur of the Biennale and to the Korea Pavilion itself, whose architecture is challenging to work with. In a small, rounded and glass-walled part of the building, she installed A New Pillar (2003), a comical engorgement of the faux-classic column that lay smack in the middle of the already small room. She highlighted the discovery of a back door that had been covered by a wall, by parking a three-wheeled motorcycle, A New Life (2003), on the threshold, blocking access to the back garden. The bike carried a plywood structure on its back, whose form approximated a two-level house and yet had plywood markings that resembled the traffic markings of a roadway. The bike made no sense in watery Venice, which is divided by stepped bridges. The house and roadway suggested displacement or itinerancy, perhaps inspired by Seoul’s massive urban transformation, the so-called New Towns initiative, which beginning in the early 2000s had sent city residents to new high-rise developments in far-flung suburbs.

This conscious but understated injection of critical social content—crucially, not through an obvious appropriation of media imagery—is one reason that Chung’s sculptures have an avid following among other artists. Hers are objects whose logic—or, more frequently, illogic—is deeply considered and layered. East West South North (2007), for instance, which was first shown in 2007 at Chung’s solo exhibition at Atelier Hermès, Seoul, is a five-by-six-meter perimeter fence, just 60 centimeters in height and painted in blue, and comprised of interconnected sections on swiveling wheels. Each gate is marked with a letter—N, S, W or E—which, as it turns out, doesn’t correspond to the actual cardinal directions of the space. Because people can open the gates and walk into the area, the whole rectangular containment structure quickly loses its shape—a kind of self-defeating object that pretends to organize and control space and movement, but in fact doesn’t at all. It might be easy to read political implications into such a work, especially in the context of a highly regimented society like Korea’s—one that is also divided by a fence into a “South” and a “North,” and alternatively conflicted about its openness to influences from both the “West” and the “East.” However, as Chung has written about her own work: “I tried as much as possible not to allow any conventional relations to appear in my work. I thought that art should perform a critical function in its cutting-edge and uncompromising state.”

III. SPECIAL INTERFERENCE FOLLOW

East West South North is a sculpture that activates viewers into becoming performers in the space. They are able to come in and out of the gates, and stand inside looking out at their friends on the outside. Most people walk awkwardly around its circumference, trying to decide if they should interact with the fence or not. The object and body enter into a relationship, with the former dictating the latter.

Chung has become increasingly interested in these active situations. Her photograph Clay Tower (2013), for instance, depicts a young man in jeans, T-shirt and flip-flops sitting slightly slouched with his arms at his side on a stool; on his left knee is a crudely hewn, brown clay structure that looks similar to a pagoda. The image captures the figure trying to keep the unstable structure balanced; the form of one structure determines the other, and vice versa. Chung reflected in our conversation that the work of an earlier professor from SNU, Insu Choi, who had also studied in Germany early in his career, had informed her practice. “He guided me to think that sculpture can house a performative aspect. In Choi’s practice, he rolled and rolled a ball of clay and formed a shape and that was it. I didn’t know it back then but now that I retrace this performative approach, what Choi showed me had a big influence.”

Many of Chung’s objects—particularly those from the 1990s and 2000s—remain resolutely self-contained. However, in newer works such as I Don’t Know About the Ear, from the Art Sonje show, the physical object—like many other technological appendages we have today—melds with a physical body and moves around a space with us. The ear was derived from an earlier performance piece called The Adventure of Mr. Kim and Mr. Lee (2010). For this, Chung had hired eights performers to remain in different postures or in loops of repetitive gestures, such as clicking a pen, for two consecutive hours in different parts of a theater space in Seoul’s LIG Art Hall. On the stage itself, a man and a dog circumambulated the slumped figures, many of whom were in disguises such as “a young woman disguised as an old woman,” “a middle-aged woman disguised as a middle-aged man,” “a man disguised as a ghost.” While most figures remained inert, audience members walked through the backstage and onto the stage around the actors—who were essentially still, like objects—rather than sitting passively in the audience.

Inverting the relationships of things moving through space is also the thrust of Nobody Notices It (2012–16), which comprises a pile of rough concrete (like a sibling of Corner Sculpture), a brown-paper bag with a pair of headphones attached and a circular cushion. You kneel on the cushion, look at the sculpture, and listen to the headphones playing field recordings from Zürich’s central train station by Swiss composer Manfred Werder. You become aware of your mind trying to connect elements of the ambient sound with the object in front of you, and it imbues the formless object with an unexpected animation. The invisible, in this context, gives the concrete shape a kind of ability—a liveliness that is perhaps itself otherwise indiscernible.

It is not just the materials, forms and location of Chung’s sculptures that refuse easy interpretation, but also their semiotic play. What makes Flower, for instance, a flower? Not its scale (two-plus meters in height), nor its color (unpainted white), nor its bulky forms (un-petal-like). Artist-curator Park Chan-kyong wrote at the time of the Outlook exhibition at Art Sonje:

As in the case of Flower, what is imitated here is not so much the living flower as a real object, but the word “flower.” The moment the flower acquires sound and meaning, or to follow Saussure, once it belongs to an abstracted system of language, “flower” will lose its vivid concreteness; what Chung aims for is exactly the subjective and creative effort or mystery that one can say is the inevitable result of linguistic imitation, the death of the vivid concreteness originally possessed by the objects issued by language, and the “speech” attempting to break out of that system.

In a similar vein, for an exhibition in Frankfurt, at Portikus, in 2005, Chung showed Campfire (2005). The sculpture is a gigantic, blue-painted representation of crossed wooden sticks and a blue orb that through its shape and location evokes a fire, but whose “cool” color refuses that association as well.

Coolness, in its many senses, is rightly associated with Chung’s works. “The experience of observing [Chung’s] works is abrupt, cold and pungent,” is what writer, curator and co-founder of the micro-nonprofit Audio Visual Pavilion (AVP), Hyun Seewon recently wrote for an exhibition she co-organized with Inyong An at the same time as the Art Sonje Center exhibition in September 2016. The AVP exhibition, which took place in the tiny spaces of AVP’s traditional hanok, also featured Chung’s works dating back to the late 1990s, furthering what Hyun described as the artist’s interest in “to what extent a space in an exhibition is to be shrunk or extended.” Just as with the Art Sonje exhibition, older works had returned, or reappeared. Wave (2016), for instance, is a clay form of a dramatically cresting swell—like that from Hokusai’s famous print The Great Wave—that had been part of a 1998 sculpture, Ghost, Wave, Fire, which Chung originally conceived as “an attempt to make endlessly moving things into sculptures.” In the same show, the glass-display-case-within-a-display-case, Showcase Showcase (2015), “posits an exhibition space within an exhibition space” as one of several works that, Hyun wrote, “upended the time of 2016.”

Just as a small nonprofit such as AVP is consciously trying to revive the artist-led spirit of late-’90s Seoul, the renewed interest in Chung’s practice seems to come from contemporaneous desires to find a new model for overcoming divisions in today’s art community, particularly between the readily commercial and the experimental. Yet there’s much more to Chung’s resurgence than nostalgia or historicization. With her interest in how objects transform the space and bodies around them, and how the “social memory” associated with things is a necessary element imputed by the audience, Chung’s sculptures become more than just physical pieces. They exist in a kind of proto-augmented reality. As you look at them in person, you are simultaneously processing the experience on multiple cognitive levels, layering linguistic elements and visual references onto the object before you. The “third form” that Chung has long pursued in her work has even begun to seem futuristic. While Chung Seoyoung’s works are being recognized for their historical significance in the Seoul art scene, her ghosts, just like the artist herself, are still very much present and able.