Networks of Objects

THE ACTIVE-STATE SCULPTURE AND THE VIEWER’S BODY

I often see exhibitions of sculpture being likened to a “stage.” Some may be uncomfortable with this connection of art to the stage setting, since it calls to mind a form of representation that applies to the forms and acting of theater. But there is no easy way to avoid the association of sculpture with something “staged.” When a sculpture is placed in a given setting, it takes up a portion of empty space with its volume; it alters the spatial structure as it guides the direction of the viewer’s gaze and the course of their movements. Through this form of appreciation, viewers may at times feel as though they are standing in a scene out of some newly created world, and they may treat the sculptures they encounter like an individual person they are meeting. Most indoor exhibition settings in particular are single “empty rooms,” while the so-called “white cube” – considered a basic part of the exhibition since the arrival of modernism – is similar to a stage in the sense that it is a place where new scenes are repeatedly created and removed. It recalls how Peter Brook described theater as something formed out of an empty space and a viewer, and the movement across space alone.

The reason I am mentioning theater here is not to show representation or narrative spectacle to be an effect of sculpture and its exhibition, but to underscore how deeply imbued time is in static sculpture. The analogy becomes a bit clearer when we understand the “movement across space” to be a work of art. “Movement” does not necessarily mean a movement that is visible to the eyes; even with a fixed work of art, there is a movement that arises within the viewer’s perception. To be sure, some of Chung Seoyoung’s work combines sculpture with time-based media such as sound and performance, including The Adventure of Mr. Kim and Mr. Lee (2010) and A Rest Without Notice (2012). But there are also various clues that lead us to detect fixed objects as being in an active state. One of these is evidence of movement: the bleeding of lines in drawn text that occurs as a plastic ruler supplementing (the artist’s) disabled hand is dropped or pushed over paper, the traces of sharp cuts in No.1 (2020) that split the wooden rod in two, and the lumps resembling a walnut missing one of its halves capture the resonance of physical and contingent forms and movements that differ from the sleek finish of mass-produced machinery. Associations of the time and movement through which the action inscribed on the sculpture must have occurred, stick to the static object, keeping the sculpture within a single state. In this sense, sculpture may be read as an archive of gestures. From the moment the initial material is first held in the hand to the point at which it sits under the gallery lights, from a tiny volume the size of a balloon to dimensions large enough to fill a container, sculpture represents the condensed product of accumulated movements. The experience of viewing sculpture includes not only the reading of symbolic meaning in the forms, materials, and chosen object, but also sculptural movements – a process of reading the actions leading up to the work reaching its physical stopping point. The temporality of sculpture is scattered over the various scenarios of action and choice that can be inferred from a result possessing material attributes.

Another clue that allows us to perceive time within static sculpture is the state that it denotes. The materials that Chung Seoyoung uses to create her sculptures include many objects with “uses”: shelves, carpets, desks, chairs, and so forth. Affording an experience that uses sculpture to raise questions about the world and encourage thought, her work consists of objects that can be perceived initially as “something.” Added onto this are her physical choices for the objects, including their materials and shapes, and the choices she makes when determining their arrangement, including stacking, affixing, and dropping. Other choices make these questions more complex. Objects are cast in materials that bear no relation to their use; text is written or carved; forms are crushed or decentralized, their balance removed or re-established. Through this process of avoiding function and its associated meaning, of adding different meaning, Chung composes complex narratives for her individual sculpture works. I will term this a kind of “abstraction” process in anticipation of the material’s concreteness. But the abstraction process is not oriented toward contributing a sense of anxiety, ambiguity, or mystery, or toward some vague emotional appeal. “Abstraction” here means that the sculpture’s meaning is composed in a complex way. It is also a device that places sculpture in a kind of unfixed state, and that underscores its movement and temporality. To read this unfixed state, this abstracted sculpture, one may refer to the way in which we view dance. When the central axis of a dancer’s movements is exposed, the viewer’s gaze infers additional momentum and linearity as it follows that axis’s movement. The momentary movements – a stable walking or standing state giving way to falling, rotating, leaping, and sliding – create dynamism through the intersection of balance and tension, and they make the questions that the artwork asks more complex. For instance, this axis is formed by the clear materials and forms that Chung establishes as her foundation. What is then created is a movement, not easily captured, that follows close behind that axis – the sculpture’s abstract state. This is a matter both of adjusting the details and of capturing the world exactly as it is. Since the problems of the world are not so simple, Chung begins the question using materials that are highly concrete, but she also crafts a complex network so that they do not remain in a dull state. Yet the networks that are crafted offer no help in terms of salvaging meaning. Rather than solidifying the object’s meaning, they have the effect of dissolving it and branching it off. This shows a perspective that sees it as impossible to draw up that very complexity radiating out around the object and refer in terms of a fixed meaning or function to an object that has been thrust onto the world.

The resulting active-state sculptures move with the viewer’s body. As the viewer looks at the sculpture, they are thinking about the sculpture through their own moving bodies. The exhibition is one of very few experiential devices in our lives that direct the act of viewing toward thought, and what mediates this is the viewer’s constantly moving body. “[The body] sees itself seeing; it touches itself touching; it is visible and sensitive for itself… . Visible and mobile, my body is a thing among things; it is one of them… . But because it moves itself and sees, it holds things in a circle around itself.”1 The dynamism of the exhibition’s sculptures is activated through the viewer. The viewer syncs their body to the sculpture’s words, meanings, and questions. Through the properties of the materials and the forms by which they are grasped, through the methods formed as the various objects are combined, and finally through the linkage with the viewer, Chung Seoyoung’s sculptures exist in an active state that reveals time and movement.

APPROACHING THE INDIVIDUAL AND WHOLE SIMULTANEOUSLY

Three wooden showcases, positioned at slightly different heights on the gallery wall, contain urethane resin-cast sculptures shaped like walnuts, arranged in “a form that is both piled up and falling to pieces,”2 under the titles Walnut*, Walnut**, and Walnut***(2020). A two-channel video titled The World (2019) places one of these walnuts against a white backdrop as it records the slow movement of its shadows amid the changing light of day. The infinitesimal movements represent the transformation and quantity of time. Various strands of association arise from the materials used to form the walnut sculpture and the manner in which it is arranged: an individual walnut, a group of several together, clods of dust rolling along the shelf, an object that harbors both stillness and movement in the light, perhaps a planetary body.

Three sculptures stand like pillars, differing in color and height. Blood, Flesh, Bone (2019), which is made of wood, has a round face inscribed with the English words of its title. Dark Red, It (2020), produced in painted metal, supports a waxed paper envelope bearing the outlines of keys around its edges Yellow, It (2020) has a small mirror attached to its base. “Blood, flesh, and bone” are the basic materials of the human body, as well as metaphors for the basic materials of sculpture. The place/thing referred to it by “it” is open to interpretation. Sculptures that declare themselves as sculptures, these works stand upright, directing their utterance outwards.

Some of the works bear connections to others produced in the past. They may re-incorporate past work like Untitled (1994), or use a photograph of an unfinished sculpture from the past as a basis for re-casting like The Same (2020). They may alter the composition and arrangement of a past work like A Long Continued Question (2014/2020), and they may be tied to issues addressed in the past. The appearance of past work in reconfigured forms – rather than recurring as it was – represents part of a process in which sculpture is not conferred finality, but temporarily thawed from its frozen state to be imbued with new form. This shows the nature of sculpture to be a state where something is always changing, and where the present is merely a matter of temporarily pausing at its current phase.

Table A (2020) bears connections to the content of another work titled The Time is Now (2012). In The Time is Now, a metal desk rests on wooden sawhorses, a sheet of glass laid above, with wooden shims of various thickness inserted to maintain its balance. In Table A, once the round table shape is established by the circular glass pane placed on the wooden stools and structures, ceramic sculptures are arranged on top. In this arrangement of Table A, the composition centers on balance. When we focus our attention on the new world illuminated when changes are applied, mediated by the form of the object whose function can be recognized as we infer the composition principles of sculpture at the center, we see a new field of meaning underpinning the object – a new network. The irregular objects positioned on the “table” and the function of “balance” that supports them invoke words associated with equilibrium: connection, structure, wobbliness, destruction, deviation, and so forth. As the actions and methods used to compose the sculpture become a basis for reading it, the sculpture becomes like a new character, as well as the dictionary page that offers an explanation of it. In a case like No.0 (2020), where a bent and broken wooden stick has been cast in aluminum and wrapped in stainless steel wire, the concept of “fixation” affords an opportunity for even mutually exclusive materials to share a setting on the basis of unexpected order and instances. There is a sharp reality that arises when these things are placed together – things that together appear improbable, somehow mutually contradictory, scooped up in a net placed over the surface over the world. The sculpture’s network is an expanded field of meaning created through questioning of simple preconceptions of “connection” and a variance that is akin to happenstance – and an attempt to depict the continuity of the world in the process.

As I referred to earlier in characterizing the connected experience between sculpture and viewer as an “active state,” sculpture is a condition that induces physical contact. It is a meeting where we contrast the distance between ourselves and the object, the materials that comprise ourselves and the objects, and the compositional principles of ourselves and the world we see – and where we find ourselves asking, “What is this?” Ahead of the search for meaning, the clear assumption is that this is an object placed in front of our body, in front of our eyes. For this reason, the artist has said, “I hope people will start from the idea that the artwork is a very concrete, clear fact, and that this is something they have seen.”3

FORM AS CHOSEN THOUGHT

Some have likened Chung’s work to poetry. At the risk of turning some readers off, it is an analogy that I will revisit here. While it is clearly addressing issues of sculpture, it keeps clashing within the “poetry” radius. One may think of poetry as regards methods used by the artist in arranging objects in the gallery space (for instance, making sure not to miss empty spaces located very up high) akin to writing poetry on the page and positioning the words while considering the spatial and semantic gaps between them, with the choices of form and the empty spaces between the different sculpture works bearing the question of how to relate the methods of poetry writing to those of sculpture creation.

To begin with, one link with poetry can be found in the shared medium of “text.” Chung uses titles that are neutral, yet seem to placidly describe the work’s situation. She draws a mass of meaning out of a minimum of words. Titles like No.0 and Table A seem like mere lists, yet they leave you with questions. As you read the exhibition title “Knocking Air,” the performativity of language that operates as the very act of producing sculpture is evoked. It is a title created by combining two crisp words that express the moment at which sculpture is formed through “thought displacing form”4: “Air” makes you think of an object that is mutable and cannot be contained, while “knocking” calls to mind the sound produced by bringing materials together through the physical movement of the hand and the weight of that process. As language, “knocking air” forges an extreme tension amidst stillness.

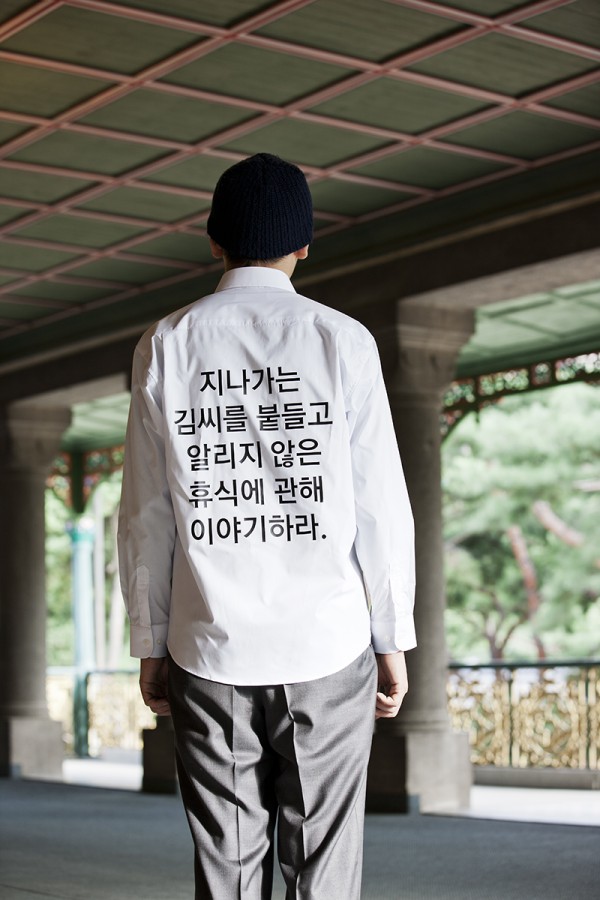

In some instances, text itself serves as a material in the artwork. In Chung’s text drawings, sentences are written on standard A4-size pottery “sheets” in pencil glaze and then fired, with the resulting work laid on one of ten pedestals of different height and three subtly different shades of white. In these works of ceramic sculpture, poetry and sculpture abut one another, with poetry becoming sculpture and sculpture becoming poetry. The pedestal represents the traditional means of exhibiting sculpture, while the texts – fired into pottery rather than printed on paper – acquire volume and properties. The bleeding of lines that occurs as the pen is placed against a ruler to draw, or as the ruler is pressed down to draw, captures a deviating, unplanned moment. As the letters are fired into ceramics, they become one and the same with their supporting surface, while the drawing solidifies as sculpture as it becomes one with the pedestal. The sentences written here also recall the compositional principles of sculpture in the sense that they seem to denote a concrete situation, yet are oriented toward an open composition in which the meaning is not clearly defined.

When you liken sculpture to poetry, you may arrive at the question of what poetry fundamentally is. It’s as large and weighty a question as that of “What is sculpture?” Accepting the fact that there are innumerable strands concealed behind it, I will define poetry as writing that uses elliptical and allusive language and possesses rhythmical form. In terms of poetry involving the extraction of the minimum necessary words – the “blood, bones, and flesh” – and using them to create rhythm, it may be connected to

Chung Seoyoung’s work, which involves establishing sculpture and creating form through the minimum necessary materials (i.e., those selected after considering what is indeed necessary). The roots of poetry are said to lie in song. Someone once said that song originated when a person walking alone on a pitchblack night began singing one to stave off their fear. I imagine the form created as that song thrust aside the nighttime landscape.