Chung Seoyoung: Along With Ghosts

“All that is solid melts into air.” — Marx & Engels, 1848

“The thought is sculpture.” — Joseph Beuys, 1969

Stepping inside of Chung Seoyoung’s world was a perplexing thing. While the entire environment surrounding the artist became an object to her, it existed before us as sculpture. Chung was responding to space, but it was a reaction to her own sculpture, not an act that was site-specific or transformed perception of the space per se. Moreover, she did not expand her objects, her sculptures, in a comprehensive sense. Her objects were present there under the name of “sculpture.” Yet people were wild about them, and I could not fathom why. Most people talked about her humor and the way it “slid” between object and language; I also think they may have been sharing their support for the aesthetic outcomes as the artist trenchantly rediscovered objects often overlooked as mere “objects” in daily life and reconfigured them according to her own strict formative principles. This was 25 years ago.

I wasn’t accustomed to Chung Seoyoung’s brand of humor, but I had two more opportunities to experience it. One came with the two-person exhibition To Infiltrate in 1999, and the other came with the work Monster Map, 15 min., which she presented in 2008. To Infiltrate exhibition was a joint effort with Choi Jeong Hwa. What I saw in this exhibition was how uncomfortable Chung was with all things solid, yet how she was also an artist who used her own robust jesting to create cracks in them. The important thing was not the humor, but the discomfort: “–Awe, if you scrub the polished skin, I think I might make a combative ikebana or something.” Within the realm of enfants terribles who make a meal of power, Chung had a different look from Choi, but shared the same zeitgeist. The two of them were also “cool” about the shared places where they could never meet. Unfortunately, the sculpture works by Chung and the art objects by Choi at the exhibition displayed no interest in one another.1

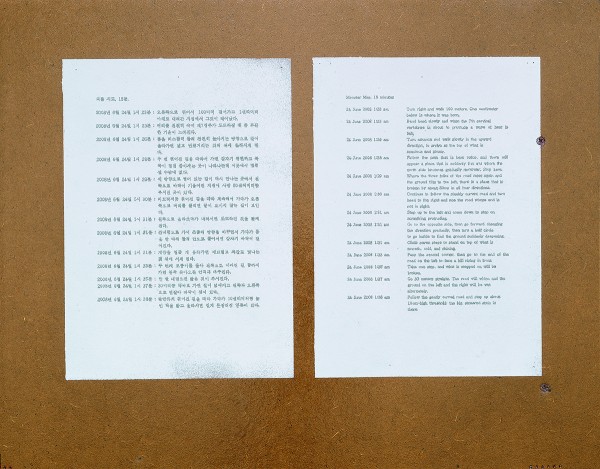

Monster Map, 15 min. alerted me to the possibility that another element underpinning Chung’s sculptural robustness might be epic theater. The work consisted of sentences from a fragmentary incident, an absurd score that took place from 1:23 to 1:38 on June 24, 2008, along with 24 drawings that seemed like they might provide a map for understanding the incident. While it may be a stretch in logical terms, I sensed a kind of similarity between the artist’s directions and the epic theater of Brecht, with its materialist clashing of incidents running counter to the poetic drama of Aristotle’s consummate structure. Once I hit on this idea, all of the exhibition titles and works that Chung had shared to date seemed like they might be a kind of epic theater along these lines to produce an alienation effect (Verfremdungseffekt) toward the viewer, the sculpture, the world, and art. Concretely, Monster Map, 15 min. made me realize its theatrical potential. Moreover, the script and picture cards seemed to suggest the artist’s sculptural intentions – contradictory though they were – of having her sculpture not exist as a sculptural act, but constantly create distance vis-à-vis the world of sculpture. In Monster Map, 15 min., her intention seemed to go beyond the level of the aesthetic, expanding into the social as it interacted with the monster of modernity. Here, I thought, was where her theatricality manifested itself. And in 2009, the artist and I brought The Adventure of Mr. Kim and Mr. Lee to the stage.

So what does the distance between objects and the theater signify to the artist? Where is sculpture situated? There is the spatial distance between sculpture/object and theater, as well as the temporal distance of 10 years between 1999 and 2009. There is no way of knowing whether this distance and time emerged from the artist, or if it was a matter of me discovering something I was yet unaware of. This text was written with the aim of gathering the differences of that distance and time.

GHOST/SCULPTURE

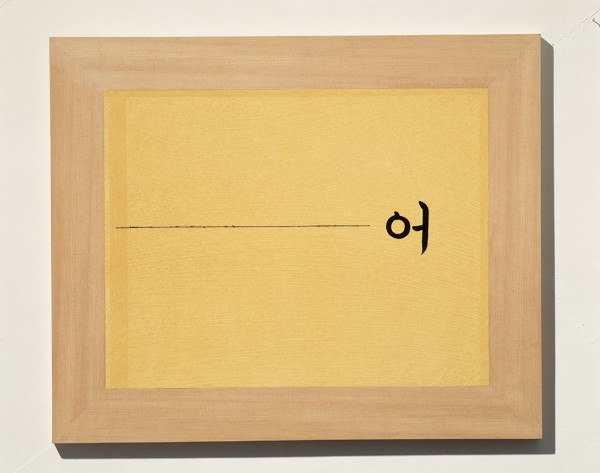

In 1998, Chung Seoyoung produced a drawing work titled Ghost Will Be Better. On a square sheet of paper, she produced something resembling a wax sculpture dribbled onto a board supported by two trestles; underneath it, the artist wrote, in English, the words “GHOST WILL BE BETTER.” More interesting than the sculpture, which seems to represent a ghost, is the writing in something like a Gungseo script. Gungseo script was used by the court ladies who worked at the palace during the Joseon era, and if we consider the insular lives that they spent – sealed off from the outside world within the palace setting – they may have come across as somewhat ghostly presences. Since their writing was also a trace of themselves, the Gungseo script may also be seen as a ghostly remnant in its own right.

The artist produced this drawing several times; in a 1998 version, she used a similar script to the drawing, but for a 2005 version she used an imitation sans serif font. To be sure, there were a few other differences between the two installation works. The patterns on the linoleum used as a floor were different, and the black plasticine of the small, ghostly sculptures was replaced with a white plasticine. Where the first version had the text written on linoleum with a hanji (Korean paper) pattern spread out on a freestanding table, the second iteration had it written on hardwood floor-patterned linoleum with a sculpture installed over top of it so that the sculpture’s table and the text’s table were integrated. Commenting on this change, Chung explained that the spatial and temporal differences between 1998 and 2005 resulted in the materials she had used being discontinued and her working conditions changing, with the new script and materials adopted in response to these circumstances. But the change in font from imitation Gungseo to imitation sans serif was significant. Where Gungseo script represents a trace of human presence, sans serif script bears the stamp of machinery. The change in sentences from Gungseo to san serif font lets us know that the sentences are not being represented as ghostly remnants, but presented in terms of their literal meaning. The situation has been materialized at the level of signification. Since 2005, these works have no longer followed along with the drawing’s script; the artist has resolved the phantasmal situation with mechanical typography as a visual representation of speech. It is not a spectral kind of change, in the sense that meaning is being declared. Ghosts don’t declare themselves – for ghosts do not know that they are ghosts.

Even so, the important thing remains the “ghost.” Ghosts don’t “get better”; if a ghost gets better, it is not a ghost. There is no such thing as a better ghost. Improving is not an objective of ghosts, but a human objective. “Ghost will be better!” – this is an impossible proposition. The ghost merely demands something. The ghost’s desires in no way have resolution as their goal; they cycle aimlessly and have no object. This is drive. The ghost’s drive is simply the satisfaction of the “ghost” object itself; it is empty, never fulfilled. If the ghost’s desire is resolved, the ghost does not return – it is no longer a ghost. And so the ghost is forever hungry, inadequate, incomplete, aimless. The ghost’s abyss is empty. “Ghost will be better” disguises the gap between desire and drive. Plausible at first glance, the words say nothing, revealing only signs. In terms of manifesting this discrepancy, ‘ghost will be better’ is a statement of the real and the present situations of jouissance.

Sculpture is inherently spectral. Michelangelo once said that all stone has a statue within, and that the job of the sculptor is to discover it. In his words, he was merely revealing to us the angel or the lovely apparition trapped within the marble. These words transform the act of sculpture into an act of religion, recalling the phenomenology of Hegel and its attempt to achieve the absolute spirit through unity between consciousness and object. But as Derrida noted, the German word for “spirit” (geist) may also signify the “soul” or a “ghost” in English and French. Consciousness and object are forever at odds, and at this level sculpture, in spite of Michelangelo’s religious convictions and artistic pride, is but a phantasm. In terms of appearance (phainesthai), Derrida refutes the general phenomenological principle on two grounds: first, that the phenomenological state of the world itself is phantasmal, and second that the phenomenological self is a phantasm.2

Chung Seoyoung continued to invoke the phantasmal. Her 1998 work Ghost, Wave, Fire speaks of three objects without fixed forms. Yellow linoleum is spread out in the center, one corner touching the wall, like a carpet over a wooden floor. On top of it are “waves” and “fire” made from plasticine. On another wall hang three drawings. One is a fabric sculpture lifting itself sharply, another is a curtain that seems to conceal something, and the third is the shape of a ghost who seems to be wearing a coat. Another drawing hangs on the adjacent wall. The curtain is half-closed. On the same wall is an elliptical shelf, with a ghostlike doll who seems to be wearing a ceramic coat. Finally, a rectangular window made of solid wood is placed at one corner, with a ridge etched into its pane.

I had always thought of this combination of three things strange; in retrospect, I see that ghosts, waves, and fire are flows of energy without defined form. In this sense, they are irregular. At the same time, waves and fire have been objects of myth as manifestations of ghosts. Interestingly, Chung gives material forms to these objects, creating a place in the process. The substance and place created by the artist produce an illusion under the name of “installation.” As Derrida so clearly stated, illusion is made possible through a return to the body, but that return is materialized as the illusion of illusion rather than a reversion to the same object.3 Ghost, Wave, Fire thus becomes a ghost of a sculpture.

Even if they are not clearly denoted to be ghosts, most of the objects that Chung has created are ghostly in the sense that they are materialized as illusions of illusion. But Stain (2007) is exceptional. In contrast with her body of sculpture/objects manifested through a process of materialization, this work had the artist pouring coffee onto a wood floor to produce a stain. According to Lacan’s concept of the gaze, a blemish is an obstacle that disrupts the gaze, but also a clear proof and sign alluding to the gaze. The artist is now showing us the gaze of the ghost/sculpture. Whether or not we are able to discover it is up to us.

THE WORK AS “ORIGINAL”

It is quite a tricky business situating Chung Seoyoung’s sculpture acts within the currents of Korean contemporary sculpture history. While we may be able to speak of individual works, it is not easy to assign a position to her work within the sculptural history’s context and trends. In terms of it being an expansion of Korean sculpture in the 1990s, Tae Man Choi assigned Chung’s work to the category of artists invoking the centripetal force of “anti-form” within the two coordinates of “concept” and “structure” from the center of sculptural tradition.4 In contrast, Soyeon Ahn described Chung as being one of the artists for whom sculptural characteristics have functioned as an important formative element amid the desire for “globalization” and installations in the Korean contemporary art of the 1990s.5 What Choi and Ahn’s assessments share is the idea that Chung Seoyoung is re-perceiving objects along the sculptural line – but while Choi describes this as “anti-form,” Ahn sees it as expanding into installation.

Such assessments are not wrong, but they are not adequate either. The reinvention of form through objects and the expansion into installation are phenomena seen previously in the members of groups active in the 1970s and 1980s: the Space & Time (ST) Group, Nanjido, TARA, Meta Vox, Logos and Pathos, and so forth. By this logic, Chung’s work could be seen as that of an artist who has realized the “1990s” achievements within the historical links of the past. What is the “1990s achievement”? Contemporary art history commentators see the movements of art in the 1980s as transition acts leading from modernism to postmodernism.6 If we accept these organisms understanding postmodernism as a contemporary aesthetic canon to be realized, then installation becomes the ultimate model of a postmodern artistic form, which can be said to have been realized in the 1990s. Such a stance is an all too Hegelian leap – for the desire towards installation cannot be signified as the completed form of the contemporary. Moreover, the expansion of the realm of sculpture had already continued its progression into space and environment since the 1960s‒1970s, passing onto the “architectural” and “non-architectural,” the “sculptural” and “non-sculptural.” If the “1990s achievement” refers to something sophisticated that suits a global aesthetic, then this is a matter of subjective taste. But if the “1990s achievement” is said to be a form of aesthetic defiance taking place within the discourse of popular culture, politics of identity, and poststructuralism, then Chung Seoyoung deviates to some extent, as she does not reflect social and political incidents directly through her work. If the 1990s is defined as an era of new media and medium-based experimentation with technological developments, then her work is not “1990s” at all, since it does not focus on form and medium experimentation, but reverts to the traditional sculptural methodology of molding, paring, and affixing.

Let us now turn to what might be called Chung’s first solo exhibition of “original work.” Chung began her artistic career after graduating from university in Seoul in the late 1980s, but the moment when she truly presented her vision as an artist could be said to have come in 1994, after she finished her studies in Germany. She staged a solo exhibition in Stuttgart, and one of the installation works in it was titled The Work Made from Several Tens of Drawings and Some Sculptures. In this title, she refers to her actions as “work” rather than as “sculpture”; ironically, the “work” here may actually be a reference to the process. In other words, she may be saying that this is a process made up of several drawings and sculptures – meaning that “some sculptures” are literally included in the work. Within the cyclical structure of “drawing,” “sculpture,” “object,” “installation,” and “work,” she positions her fragmentary experiences and memories within space as drawings and sculptures-as-objects. This is “work,” but it is also a work of art and a staged situation. It mocks “installation” as little more than a decorative interior, while referring to Chung’s own installation as both “work” and “a work.”

While there is no way of examining the drawings installed, they seem to represent the research into the objects’ situations and states, and Chung used the drawings as a basis for four sculpture installations. Hands grasping a bar in a sculpture that seems to represent the “hold tight” pictogram shown for safety purposes on bumpy public transportation (Untitled, 1994); an object that may be pottery or sculpture, bearing an image of a strange intersection on a tilted white ceramic vase (On the Vase, the Street, 1993); a sculpture stacking two small, black canisters that represent the same unit in different sizes (The Sculpture with Rubber Band, 1994). In the last of these, the small canister at the bottom of the sculpture has rubber band handles attached on all sides. Finally, there is a pseudo-flagpole sculpture with heavy herringbone patterned

fabric draped over a coat stand, which is presented so that it oddly seems to be jointly holding up a three-tiered wooden shelf (Untitled, 1994).

All of these objects react to movement. The safety bar is gripped to resist speed; the leaning vase features an image showing a way back out. At the base of the two stacked canisters, the handle-like rubber bands would cause the objects to come apart if pulled. The two racks support each other precariously, but the flag-like cloth occupies the top part of the structure with its immobile posture. The tension between movement and stillness coexists within the contradiction of “a work/sculpture” and “work.” The artist seeks not to express movement, but to present contemplation of movement in a sculptural way. Sim Sangyong characterizes this approach by Chung in terms of sculpture and division: “To the artist, sculpture may only be itself through division; it may only approach through abandonment.”7 This observation appears appropriate in the sense that Chung seeks to deconstruct the concept of sculpture – but it seems somehow inadequate to explain it in terms of “deconstruction.” So what is the concept of sculpture she is defining through deconstruction, and what is the standing of sculpture that she hopes to claim in art history through this concept?

Joseph Beuys said something interesting about sculpture in a 1969 interview with Willoughby Sharp.8 Maintaining that the truth of sculpture as a very complex creation had been ignored, he named “thought” as the origin of sculpture, based on the fact that it offers definitions to people. “The thought is sculpture,” he said, explaining that the sculpture already exists with the formation of thought. There are many implications to this. In positing all human creativity as sculptural, he is describing all creative acts that involve breaking something down and building something new – be it tangible or intangible – as “sculptural.” From there, Beuys progresses to social sculpture. But ahead of that, he says that the meaning of sculpture is precisely encapsulated when we respond to the question “What is sculpture?” with the answer “sculpture.” For Beuys, all sculpture until now has been products of creative capital in miniature.

How might sculpture be expanded? For Chung Seoyoung, this is a matter of invoking the sculpture referred to by the name “sculpture,” placing it in opposition to objects and creating the illusion of “objects of objects,” “sculptures of sculpture.” From her standpoint, sculpture is something that has never been realized, but it is a real thing that unquestionably operates within reality. She is aware of how sculpture in the modern sense has discarded or expanded its foundations, by its own volition or otherwise. But sculpture exists here without reality. Chung invokes sculpture as this sort of ghostly object. She is not summoning the ghost into sculpture, but summoning the sculpture here and now in its spectral state. Her summoning is not meant to revive the ghost or enable its ascension. Rather, it reveals the truth of the ghostly state of sculpture to be an “illusion of illusion.” The core of her sculptural act is thus the summoning of a ghost.

In an interview, Chung described the process of making Lookout (1999).9 She related the physical process of realizing an image of an observatory from a postcard as a sculpture within actual space. But this was not a physical process of “realizing an image”; she explains that she was giving form to the physical distance between object and artist. In other words, the incarnation of the image lies not in the image of itself, but in the distance that the artist and the embodied image must find. Finding that distance, she explained, is her sculptural process. This admission seems less a statement of her convictions, her intent to embody her object, than a commitment to producing the distance of illusion in order to manifest the ghostly object of the image. In other words, the artist’s intention is to find the distance between a person and a ghost. In terms of summoning of a ghost, Chung Seoyoung’s sculpting process could be seen as a process of mourning – but that mourning is not something resolved through sculpture. Instead, it locates the most suitable distance between the sculpture and the self, the ghost and the self, and manifests that distance within reality. Through this distance, the sculpture is sealed into reality in its ghostly state. This could be seen as a very cruel act toward ghosts or sculpture; in that tense, it may not be mourning.

In this regard, Chung’s sculpture is neither “anti-form” nor “non-sculptural.” By summoning the ghost of sculpture and producing the distance between the ghost and the self, she is manifesting the fissure between the ghost/sculpture and the time created by the object. It is a conceptual stance, in the sense of its reflection on sculptural history. But in terms of locating the existential conditions of sculpture within the distance of the ghost – without abandoning the element of “making something” – it does not betray the traditional act of sculpture either. Sculpture is always a matter of distance with regard to the viewer. In its scale, sculpture is not existential, but forever surrealistic.

To Chung, sculpture is something quite natural and universal, but the real-world sculptures that she confronts are too solid, or perhaps they are objects that watch us even as we cannot see them. Sculptures of the former kind represent the reality of “sculpture” as defined by the sculpture community that Chung has experienced in Korea; those of the latter kind represent the current state of contemporary sculpture that has already passed over into an expanded realm. At these two positions, she constantly reverts to sculpture. The first reversion involves deconstructing the historical weight of sculpture and reducing it to an object, but it is then presented with the grammar of sculpture. The second reversion involves embodying the distance vis-à-vis the ghost of sculpture within the exhibition setting. Through that distance, it is not the ghost/sculpture that observes us, but we who observe the ghost/sculpture.

The “ghost of sculpture,” “embodied objects,” and “distance from the ghost/sculpture” – these three elements may serve as a basis for speaking of the ontology of Chung’s sculpture as “hauntology.” The ghost of sculpture arrives from the past to manifest in the present, but it possesses no reality. All that remains is the weight of history that seems to have finished. The artist conveys the sculpture’s past substance through objects, but what matters to her ultimately is not embodiment of the object, but the

distance between the world and the sculpture as an incarnation of the manifested ghost. Within the gallery, that distance is reduced into the distance between the viewer and the ghost/sculpture/object. Within that distance, sculpture is deconstructed and recombined. What the distance produces is the understanding that the contemporaneity of sculpture is always non-contemporaneous. And this is where Chung’s sculptures manifest. She is not guiding us to experience a hitherto-unknown logic of sculpture; it is a form of hauntology where the object and the ghost of sculpture returned to the present result in Chung’s sculptures intrinsically manifesting the experience of distance from the incarnated “thing.”

The ghosts do not reveal their presence clearly between existence and absence or appearance and disappearance; they hover between material embodiment and disembodiment, residing in a purely virtual space, and the virtual space created by that distance is taken over as the existential foundation of the ghost/sculpture.10

FROM GHOSTS TO MONSTERS

The ghost has become a monster. This is a highly significant moment, for it means that the artist is now dealing directly with the world of materials. She removes the distance of the ghost – in other words, the sculpture’s distance. She moves from the world of the sculpture with the name of “ghost” to here in the physical world. Monsters and ghosts are similar in that they both inspire fear, but they differ in terms of their existence. Monsters are patently material beings. A ghost is something that has died, but is not fully dead. Ghosts possess no material presence; this is not the case for monsters. Monsters truly exist. Yet monsters are assigned according to judicial-biological concepts that distinguish “normal” from “abnormal.”11 A monster is defined as a monster through judicial determinations that assign abnormality. The discovery that something different is a monster divides the inside of a community from its outside. This does not simply refer to the physical distance between a community’s inside and outside; it implies the possibility of something being legally judged to be a monster within a community at any time. In other words, monsters can be found inside at any moment, and their determination is always ideological. The shift in the artist’s attention from ghosts to monsters suggests her intention of going from an interest in the distance between ghost sculpture/object and self-viewer to addressing the principles of power that draw the boundary lines between an object and an object, and between the self and the self. Power possesses directionality, which in turn constructs space. This then elicits physical outcomes. Chung’s interest has transferred from the distance of ghosts to the time of monsters.12

This movement can be said to have begun out of physical signs. Chung experienced a disconnect between consciousness and object through her own person. Nervous system errors of unknown provenance took a physical toll on her body, giving rise to malfunctions. Monster Map, 15 min. is based on this experience. It is an excruciating thing to physically experience the disjuncture of mind and matter. Throughout our lives, we find errors in the mental and physical worlds. The reason we are able to accept those errors is because we are able to find suitable distances between them. But when these distances flatten and are experienced through our bodies, the results are tragic – for the disjunctures of the world arise within the subject. But Chung expands this experience into the realm of the social.

The Adventure of Mr. Kim and Mr. Lee (2009) is a real-time response to Monster Map, 15 min.13 But it does not merely embody the monster map realized through text and drawing. As a text, Monster Map, 15 min. limns a space that is encountered through movement. Traces are recounted in the spaces encountered – evidence of birth and absence. An incident is referred in the text, where something breaks as it is stepped upon. In terms of an action that produces an outcome, this is an event, but it is portrayed like a physical phenomenon, and that phenomenon is “being out of joint.” A dislocated situation, a discrepancy that happens the instant we enter, whether it is intentional or not. The contemporaneous meaning that Chung sought to show through distance is now shattered. Something will now appear there – a monster is discovered.

At the same time, the drawing work in Monster Map, 15 min. offers a visual cryptogram for these narratives. The drawings mostly include fragmentary objects and spaces, but there are also sentences that the artist has clearly written and included in text form. This is The Adventure of Mr. Kim and Mr. Lee.

THE ADVENTURE OF MR. KIM AND MR. LEE

“Mr. Kim: That was an enormously large rock. He was scheduled to leave soon. He was just about to rush off after getting into a fight with someone.

Mr. Lee: That isn’t a song to sing when you’ve been shaken by some lightly blowing dust storm. But now he’s staring like he’s about to get sucked into the sweat on that loyal guy’s forehead.

Mr. Kim: Your knee broke after two laps.

Mr. Lee: I’ll cut a bit off the brim of your hat.”

These sentences merely present signs, without narrating any incident. The disjointed dialogue between the two men reveal signs of the power of an unrealistic world rendered visible. The symptoms form three-dimensional coordinates with a particular directionality, creating space – territory, in other words. The territory that is built will clearly impose a physical force on us; here, we may find ourselves branded “monsters” at any time. We are discovered to be monsters, or we become them ourselves.

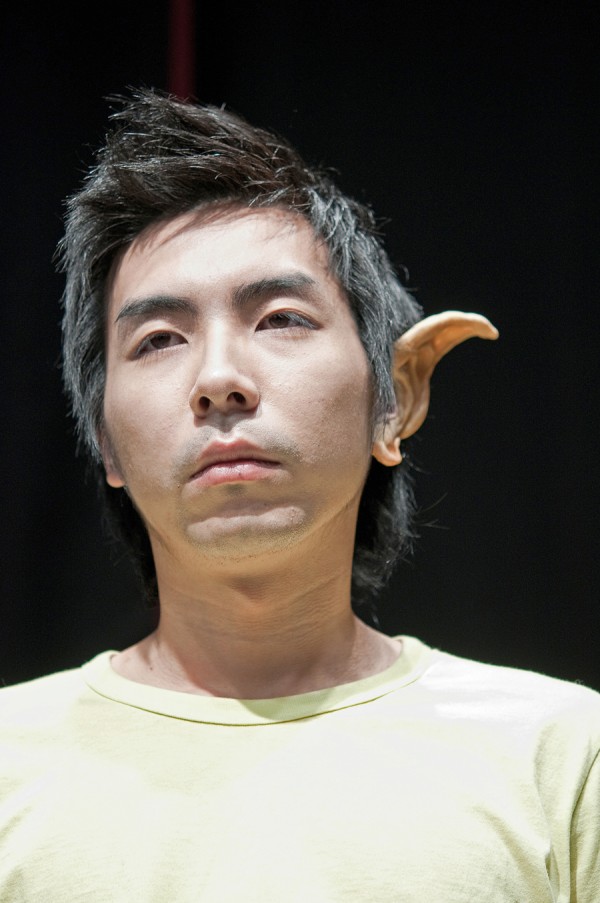

The performance venue, which includes seats, a stage, and a makeup room, is not yet a space that has been territorialized by new power. It is a black box, a literal dark cavern. Visitors enter that world not with light, but with sound; what aids us are auditory devices rather than visual ones. Unable to rely on light, we must focus our hearing on the sounds. What the viewer sees is a young man 1, a young man 2, a short young woman dressed as a child, a young man dressed as a monster, a dog and its owner, a young woman made up like an old one, an Asian man made up like a Western one, a young man made up like a woman, and a middle-aged woman made up like a middle-aged man. Their impersonations are not impersonations, but reality. They are positioned in the theater as signs of a sort, visible or invisible. Some of them are visually different, and some of them have normal exteriors that offer no hint of what is within. At its core, the performance is not about finding the bases of “monstrosity” in the world, but about making the viewer realize the impossibility of comprehending monstrosity. What the artist seeks to show through the removed distance from the ghost/sculpture are the signs of the “normal” and “abnormal” that are imposed in all spaces by legal mechanisms; she is rendering strange the ideological illusions concerning belief that operate in the real world, and in the process she makes us aware of how our own lives exist in kind of a theatrical state.

The living objects that appear in The Adventure of Mr. Kim and Mr. Lee differ from the objects in an existential sense, as seen with artists ranging from Piero Manzoni to Gilbert & George and Marina Abramovic. Their living objects reconstruct the concepts of the “artist” and “artwork” within the artistic establishment. But the characters in The Adventure of Mr. Kim and Mr. Lee are “living objects” themselves. They make no attempt to prove their own existence; rather than demonstrating their own existence, they manifest a state of being without proof. In this respect, their characteristics echo those of monsters. Monsters are already with us, but they are only branded as “monsters” when a judicial decision finds them to be in the abnormal state of monstrosity. So these living objects represent the literal etymology of the word monster, situated at the extreme of the “monster” boundary as it has been arbitrarily defined, existing there as presences warning of something to come. They are either already organisms or already sculpture.

After the monsters, the next most noticeable element in Chung’s work is the use of mirrors. The artist has often incorporated irregular polygonal mirrors of various sizes in her installations; examples include Night and Day (2011) and Inwardly, Determine Yourself (2012). The large mirrors placed against spaces and objects reflect the world. Recalling the story of Medusa and the mirror, we may view the placement of these objects as a natural consequence. The monster will be sealed away in the mirror, returning as the ghost of sculpture.

Let us return to the sculptor Chung Seoyoung. For her, sculpture is something natural and universal. Paradoxically, however, sculpture is also frightening and strange to her – for sculpture is one enormous phantom. But rather than trying to capture that phantom, she has tried to build a distance from it. She has believed this to be a way of opening up the possibility of pulverizing the phantom without fetishizing it. Ghosts will always return, but their true form is empty. If we recall the words of Joseph Beuys, we see that we have never encountered sculpture. And so the place of sculpture from which Chung Seoyoung has departed is not the place from which she rightly should have departed. To Chung as well, the ghost of sculpture is in reality the uncanny (unheimlich). The significance of the world she has shared to date lies in her efforts to begin her sculpture out of that uncanniness. Most artists will ignore it, visualize it, or exult as though they have overcome it.

Chung uses distance to embody the true form of the ghost/sculpture that emerges through her reflection on sculpture, and in the process reveals the phantoms of contemporary material life. The objects have been found as a way of deconstructing the authority of sculpture; the language has been a game to disrupt our perceptions. Distance is a space that manifests Chung’s sculptures within this process. It is

simultaneously real and virtual. The ghost/sculpture-sculpture/object-distance/space has been transposed to the monster/society; it now takes over Chung Seoyoung’s present in a cycle of ghost-sculpture-object-monster-society. To the artist, making something is now no longer simply a matter of building an object through matter, but the performance of a creative critique of the world.

We must not force sculpture on Chung Seoyoung. We must ask her to welcome sculpture as an uncanny that exists in a deeper place. Not mourning, but welcoming, for ghosts always return. In a recent interview, Chung told me that the hierarchy of objects has changed. It sounded to me as though she recognized a change in the role or discussion of objects in contemporary life. This idea that the hierarchy of objects has transformed implies the hierarchy of sculpture has unquestionably changed for the artist, and that the hierarchy of the world has been unsettled once again. The ghost has made its reappearance. And Chung is saying that she will confront that new unheimlich. Returning to Derrida’s hauntology, we should recall a passage from Shakespeare’s Hamlet that he included at the end of one of his books. Derrida does not end his book with the ghost, but with a recommendation for a dialogue with the ghost.

“Thou art a scholar; speak to it, Horatio.”14

-

In this regard, the exhibition was a failure for the two artists, but an important exhibition for the art space that invited them as it heralded their transformation. Having

sought to “independently” achieve an escape from the critical art of the 1980s, the institution attempted to represent the impossible goal through the encounter between the two artists. To invoke terms popular at the time, they invited two artists in the name of “purity” and “kitsch.” The reason the exhibition’s title referred to “to infiltrate” rather than “clashing” or “exploding” reflected the space’s hope for a “permeation” of the two artists’ approaches into the institution itself, rather than permeation between the artists. ↩ -

Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx, Koreans trans. Taewon Jin (Seoul: EJ Books, 2007), p. 263. ↩

-

Derrida, pp. 246–247. ↩

-

Taeman Choi, Study of Korean Contemporary Sculpture History (Seoul: Art Books, 2007), p. 616. ↩

-

Soyeon Ahn, “Changes in Korean Contemporary Sculpture amid the Internationalization Trend in Installation Art, 1980s to 1990s,” Journal of Korean Modern & Contemporary Art History 36 (Dec. 2018): pp. 247–248. ↩

-

Honghee Kim is among the most representative figures asserting the art of the 1990s to be “postmodernist” according to this perspective. Honghee Kim, “Korean Art of the 1980s: Transitional Art between 1970s Modernism and 1990s Postmodernism,” Korean Contemporary Art 198090 (Seoul: Hakyoun, 2009), pp. 13–37. ↩

-

Sim Sang-yong, “On Sculpture from Division,” Art World 153 (July 1997): p. 31. ↩

-

Willoughby Sharp, “An Interview with Joseph Beuys,” Artforum 8, No. 4, (December 1969): p. 47. ↩

-

Hyejin Ju, “To Move from an Uncertain Place Is to Be Candid,” Article 34 (May 2014): p. 29. ↩

-

This sentence is an altered version of Christopher Prendergast’s definition of Derrida’s hauntology. Christopher Prendergast, “Derrida’s Hamlet,” SubStance, Issue 106 Vol. 34 (No. 2005): pp. 45–46. ↩

-

Michel Foucault, Abnormal, Korean trans. Jeongja Park (Seoul: Dongmunseon, 2001), p. 75. ↩

-

Regarding Monster Map, 15 min., the artist has explained, “My interest is not in the ‘monster’ per se. I’m interested in the idea of the concreteness of ‘direction’ and ‘domain’ being created by the ‘irreality that is constantly appearing within reality.’” ↩

-

I curated this production. While Chung does not appear to perceive Monster Map, 15 min. as a theatrical object, I felt that it should operate as theater rather than being exhibited as sculpture. I later had the opportunity to exhibit in a theater, and I felt that this work should be staged there. Chung was quite baffled about the idea of having to “stage” as opposed to sculpting something, but she resolved things in a sculptural fashion. ↩

-

In Hamlet, these lines come from a conversation between Horatio and the sentries. Having seen the ghost of the late king, the sentries tell Horatio about their experience; while he disbelieves them, they escort him to the place where the king’s ghost was seen. The ghost appears, and Marcellus urges Horatio to speak to it. ↩