An Interview with Seoyoung Chung by Ms.C

Ms.C: The composition of your work and display method was incredibly provocative, having caused a sort of “lightening effect” on the South Korean art scene of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Your artistic practice had such a striking influence on some members of Korea’s art circles—including me, of course—but was treated with complete misapprehension by others. Seoyoung Chung: Lookout, your 2000 solo exhibition at Artsonje Center, Seoul, was typical in a sense that it stimulated these polemical, bifurcated responses. Most visitors responded that they were simply unable to understand what the works were about and why much of the exhibition space was left empty. Nevertheless, the exhibition offered an indelibly important artistic experience to some artists, curators, and young people in the arts. Given that it was as late as the middle to late 1990s that the proper field of contemporary art began to take shape in South Korea, I believe your work at that time exercised a strong cognitive shock and a “lightening effect,” particularly for young emerging Korean artists who had just entered the scene. I myself am among those still under the “spell” of your work in a positive sense. But perhaps because the initial shock was too powerful, I became less diligent in keeping up with your new works, except for those exhibited at the Portikus, Frankfurt, and the Gwangju Biennale. Even though I declare myself a fan of Seoyoung Chung, I may have unwittingly helped fix the meaning of the so-called “Seoyoung Chung’s work” rather than exploring some new meaning in it. To break through this deadlock, I am going to resume the conversation about your work.

Throughout this interview, you will often come across both my understandings and misunderstandings, some of which will be far deeper understandings and some of which will be inconsistent questions. “I,” who is leading this conversation today, is basically a split subject—a single body consisting of seven different curators. So, as a result, I/we cannot exclude the possibility that my/our conversation will end without getting to any concrete understanding of your practice. Yet still, my expectation is that you will at least be able to give answers just as wise as your works.

First, I would like start with Two-Artist Exhibition: Jeonghwa Choi and Seoyoung Chung (1999), although it was held a long time ago. This two-person show was significant in that it was not only the first Korean exhibition to introduce your work to Korean viewers, but also in that it was the inaugural show for Art Space Pool. However, the result was frankly a serious mismatch between the two artists. I mean, it was a mismatch of nonsense that miserably failed, not the kind that was ironic and thus created something new through its rifts. What is your own view on the exhibition?

Chung: The conception and inauguration of “alternative art spaces” was quite a meaningful event in 1999 Korea. After the inaugural exhibition of Art Space Pool, Choi and I were invited once again to have another inaugural exhibition—this time at Alternative Space Loop. As far as I can remember, the curatorial intention of the 1999 show at Pool was to bring up the questions that should posed to the Korean art scene of that time by creating a brutal contrast between Choi and me who respectively represent, say, non-art and art, or two kinds of innovation in starkly different directions. To answer this question, I revisited the essay that Chan-kyong Park, one of the key members of Pool, wrote for the exhibition. There, he said that he expected from this project an intelligently sustainable schema, not pyrotechnic synergy. With the occasion of this exhibition, he also noted, Art Space Pool should draw out more fundamental questions about art and eventually focus on overturning the simple question about the boundary between art and non-art. But when I look back now, the exhibition format was somewhat boring and mediocre, failing to meet Park’s expectation or the radical potential endowed to Korean alternative art spaces at that time. The artists, as well as the curator, might have been too optimistic and had no idea how to innovatively use the medium of art exhibition. We all did nothing other than simply depending on the capacity of the artists or the “aura” of their artworks. But my honest view is that Choi’s and my works at the show were not that much opposed to each other. Choi and I were of course extremely different in our approach to art-making; but our works, when on display in the same space, did not create a particularly interesting conflict, probably because, for better or worse, we were alike in intentionally rejecting authoritative-looking forms of art. In other words, the curatorial concept of contrasting art and non-art was, from the beginning, unnecessary. Rather, what was more interesting were the positions that the alternative art space had expected of us when it chose us to exhibit there, which I think revealed what was lacking in Korean art at that time.

Ms.C: The above-mentioned “lightening effect” also signifies that your work played a certain role in the period when the field of so-called “contemporary art” evolved rapidly in Korean during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Indeed, this was when the symptoms of the “turn to contemporary art” became apparent in a group of artists, which includes you, the late Yiso Bahc, and other fellow artists working at the time. Although it is not officially recognized, there is no doubt that your friendship and the mutual influences that you had on one another, both in art-making and personal lives, have set the stage for the field. Could you tell me with whom, among the artists working in the 1990s (and now), were (and are) you able to share your inspirations and thoughts on art? And if there was a sort of consciousness shared by the artists then, what was it?

Chung: After returning to Korea in the late 1990s, I spent delightful times with many artists such as Yiso Bahc, Chan-kyong Park, Kyuchul Ahn, Hongsok Gim, Sora Kim, Jewyo Rhii, Nayoung Gim, and others. However, as life goes, it’s hard to say that to this day all of these individuals remain my colleagues in the same sense as before. At that time, the most essential common ground shared among us was the need to announce, through public art spaces, the type of artistic language that had been nonexistent or continuously overlooked in the Korean art scene.

Ms.C: Looking back at sculpture-making in 1990s Korea, it seems that “installation art” emerged as an important trend and was highlighted as a new art form, though emphasis was still placed on traditional sculptural methods that deal with the materiality of media and the representation of form. Your work, however, does not appear to belong to either conception of sculpture. It could be said that your works also have something of Minimalist sculpture or installation based on their spatial expansion and the way you take the entire exhibition space very seriously. Nevertheless, your work is still at a distance from the stylized installation art that was largely practiced in Korea in the 1990s. In this context, I would like to ask you about the sculptural styles or dominant trends that you learned in college or art schools in the 1980s and 1990s, that is, during the early period in your career. How did you start your career in such an environment? What influential factors have shaped the development of your practice?

Chung: The department of sculpture at Seoul National University from which I graduated had a curriculum rigidly based on a traditional understanding of sculpture. I was enthusiastic, but found it very hard to stand this situation in which a single view of art exercised too much authority. It was in my sophomore year that sculptor Insoo Choi began to teach us and introduced us to a previously unknown, more flexible attitude toward sculpture. I think this was when I, though vaguely, got the hang of thinking of sculpture not as a finished form but as a process—in which the artist’s idea pushes out a form—while still remaining within the frame of traditional sculptural form. From then, I continuously tried to manifest this vague feeling in a more concrete way—in reality—until the mid-1990s while staying in Germany. But it was only after I returned to Korea that my work got really serious. Korea in the mid-1990s was different from the 1980s; it was so open that it could allow new and unprecedented elements to appear in society. These developments helped point out some of the long-pending problems of Korean society. The discord between these problems suddenly caught my eyes again. Thinking constructively about these ridiculously funny yet depressing issues, I found ways to develop my present work.

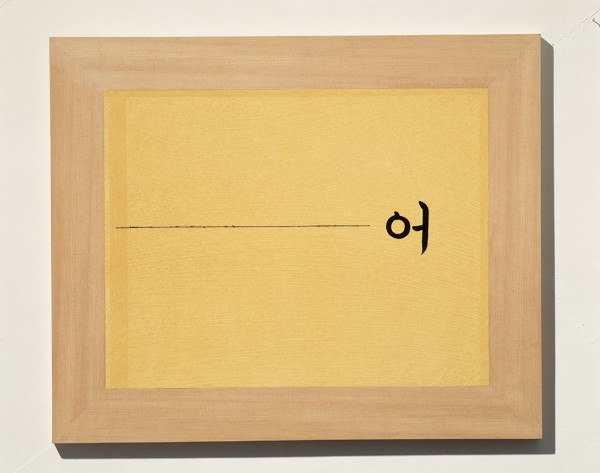

Ms.C: As far as I understand, non-relational relations and recording private existential coordinates under the pretense of objective diagrams are distinguishing features of your work. In your 2000 exhibition at Artsonje Center, your aversion to “depth” was so emphasized that lights with warm colors suggestive of depth had to be replaced with white fluorescent lights to evoke a sense of nakedness and shallowness. Your antipathy to depth was almost unconditional. However, although you took advantage of the objectivity or anonymity of the sign/object with feigned indifference, you seemed like a poet who reforges personal or collective symbols from their fixed interpretations when you dealt with the words “flower,” “fire,” “waves,” “light,” “gatehouse,” “lookout,” and so on. You may disagree, but this kind of approach occasionally seemed to indicate an expressionist wrath that the artist, as an advocate of the absolute value of the Idea, threw against a damaged value production system. Don’t you think that your attitude of auterism is directly opposed to your professed rejection of depth or your challenge to transcendentalism?

Chung: The “depth” that I denied at the Artsonje exhibition was an “unshakable obsession with meaning feigning depth” or an “authority that is simply old.” This was directed at the thick-skinned spectacle of Korean art at that time and was also related to my refusal of the conventional semiotic interpretation of art. So I tried as much as possible not to allow any conventional relations to appear in my work. I thought that art should perform a critical function in its cutting-edge and uncompromising state. This uncompromising attitude was not a belief in authorship dedicated to absolute value but an attempt to act on the system of fine distinctions between things and events.

Ms.C: What was the source of the sinister feeling emitting from your earlier carbon paper drawings? Was it the foreboding of schizophrenia or the fear that the traces of carbon would disappear from the paper? Or was it the anxiety that the drawn figures would not remain on paper but instead forcibly multiply within us?

Chung: Those drawings deal with fear itself. They are imaginary paintings that are gloomy and sometimes absurd rather than sinister.

Ms.C: Your exhibition titles that have no apparent relation to your works are very distinctive and unique. As suggested by such exhibitions as Lookout at Artsonje center and On the Top of the Table, Please Use Ordinary Nails with Small Head. Do Not Use Screws at Atelier Hermes, almost all of your exhibition titles seem to be play a certain role. In contrast to the fact that Modernism in art was marked by its anti-narrative qualities, your work has good command of both the moderate Modernist language—that is, geometric or physical plastic language—and narrative language. This narrative or quasi-narrative wording appears quite prominently in the titles of your exhibitions and works, and even within some of the works themselves. I thought to myself what it would be like if there were no titles for your works. The first thing that came to my mind was that I would no longer need to rack my brain or drive myself crazy. You may ask in return what there is to make me rack my brains. Walter Benjamin insisted upon the importance of titles for the politicization of photography, but in your case, won’t the audience or readers more likely be in a state of drift if they are hooked by your titles? I would like to hear the reasons why you use this narrative language, and why you bring together seemingly oppositional languages in your work.

Chung: Let’s start with the phrase “command of both the moderate … physical plastic language and narrative language.” If you want these two languages to go together, you need to understand the hidden relationship between them as well as the role that uncertainty plays in the drawing-text. The particularity of achieving this understanding will reveal itself in how one makes this relation “unrevealed” and where one cuts off the sentence. It is more important to notice what newly appears from the state of being unrevealed rather than to guess what it is that is left unrevealed. Anyway, due to this kind of disjunction, a drift or a strained leap occurs. If words do not indicate something, are they an empty language? If you think so, you will drift away. However, if you can enjoy the stream of thought running through this type of phraseology, you will make a leap. The speed at which you are brought to this ultimate leap is sometimes fast and other times gradual. In most cases you are invited to endure an extended period of time (consuming the words) because of the oppositional methods of narrative, and the best way to spend this time is to reduce unnecessary burdens. Even so, you may ask me, “Well, if I spent this time successfully and finally made a leap, so what?” My answer would be this: you can recognize newly-reorganized relationships between objects and yourself, and you become aware of the seriousness and humor of the pebbles, murmurs, and intermittent sounds that stand shoulder to shoulder with you.

Ms.C: Whether in sculpture or drawing, I find the materiality of your work very provocative, especially when the works appear to be popping out of the space of the white cube. It seems to me that it is actually this material presence in the white cube that offers visitors an intense encounter with your works. May I call this a kind of elaborate condensation of poetic insights into form? If I see it face-to-face logically, it will most likely fall into disarray. What meaning does form have for you?

Chung: A long time ago, I called my works “things.” I cannot take my eyes off of the matter and things that fill the world. They are very real. The reality of matter and form. Those things that brazenly occupy space and intrude into my time are, so to speak, a kind of evidence. Evidence of what? They are evidence of the fact that people always have their noses in what makes something “exist,” and that they do so by leaving something out. I observe this evidence. My sculptures are the evidence that shows that I extensively observe these things and think about them. I have a clear understanding that my sculptures are also matter. Thus, to make them clearly materialistic, I think about the state of matter over and over again. For me, form is a clearly-chosen thought.

Ms.C: This may be too big of a question in this context, but I wonder about your thoughts on objects and sculpture. Ah, before that question, are you a sculptor?

Chung: Generally speaking, I am a sculptor. And that is truly too big and loose of a question, as you said. Even so, I feel I can insert into the looseness this statement: to proceed from objects to sculpture, you have to break the “consensus” regarding things.

Ms.C: What consensus regarding things?

Chung: Whew… This is the part that I find the most difficult to explain. Here, “consensus” describes the beliefs about objects, such as the known facts about them, the limits of the expectations about their future, and so on. Once you get to know this you’ll find it quite common.

Ms.C: Nothing is free of “defects,” whether an object, a language, a body, a social system, or anything else. Personally, I often have the impression that your work is about revealing defects and that you have no intention of condemning—saying “this is defective!”—or asking about defects. On the contrary, you at times make enjoyable use of defects, and at other times create a work full of defects with a perfect mastery.

Chung: Hmm… Let me first consider what it means to “create a work full of defects with a perfect mastery.” Most of those who know about my works will say, “That sounds vague. Ah… maybe?” and those who do not will say, “Well, is there such a thing as that?” In your phrase “a work full of defects,” the “defects” might also be understood as already-modified defects. Since the lack of clear differentiation between these two kinds of defects might cause confusion, do you mind if you would rephrase that I create “a work full of thoughts on defects”? It is of course impossible to create a work of art that has no defects, but a work full of defects sounds… but at any rate, I “agree.” I remember having said, “I am given to guessing, misunderstanding, and discovering about objects and trying to make it known that they can keep balance with all the other things in the world.” To dwell on this would be like this: “I am thinking about the limited life to which obvious objects paradoxically awaken us, and even though I cannot eliminate defects through my work, I make efforts to create a special time to finally deal with them.” Recently, a man who jumped from the stratosphere is making a lot of buzz. He said that the most nerve-wracking moment in this adventure was when he was about to jump, and the most beautiful moment was when his feet touched the ground. As for me, I find him quite perfect at the very moment of saying that. The striking words of another stratospheric skydiver I heard a long time ago–that he had jumped “to face the earth”—suddenly comes loose.

Ms.C: As you know, countlessly many fragments of the private symbols (including both objects and words) that appropriate the collective symbols of social reality are hanging around in the field of the so-called “life-world” of artists. These anonymous private fragments floating separately give rise to an impatient desire to expect a narrative context. What is more dangerous than this impatience, however, is the possibility that these countless fragments of objects/words will ultimately turn into simple data or information. If the overabundance of information reaches its limit, like in Japan, wouldn’t it be possible that the Symbolic and the Imaginary (which is supposed to overwhelm the Real) coexist in practical terms without any additional explanation? Is there a narrative that you have built in spite of yourself? You may answer that you have not, but … I frequently imagine that one day a pretty lyrical diagram will be made out of Seoyoung Chung’s “mind map” that begins with one of your earliest works, Awe (1996).

Chung: What is at the crux of the phrases—that “countless fragments of objects/words will ultimately turn into simple data” and that they come to “coexist in practical terms” with the Real—is: the word “private.” It is not important whether or not there is a narrative; but it is problematic if art gets excessively “private.” This is because art should be independent as much as possible but equally should not be shut in a world that has shrunk into private closeness. And it is not a matter of importance whether there is a narrative in my work. Of course, it undoubtedly has a stream.

Ms.C: Your works, whether objects or words, have a strong substantiality, but yet they steal their way into the weak ties between reality and a system of meanings to disturb them without depending on the materiality of materials, play with scale, feats of processing, and symbology. This kind of “reading” could be available in the case of a single work of art as a kind of arbitrary sign, but when many works are placed together to build “Seoyoung Chung’s space,” they are set into a more complex situation. This situation involves the inevitable relationship with the context of the given space, that is, the sticky placeness—paradoxically, its slushy “depth.” This is why Chan-kyong Park called the seemingly arbitrary display as creating a state of “coexistence-for-the-self,” placing it at the opposite end of the stylized interior that is unabashedly engaged in processing meanings. Furthermore, he went as far as asking: “to what extent will Chung’s objects be able to baffle art as the institution?” But of course he himself couldn’t answer this question. (Laugh) To put it plainly, it was in this time that I got the clue that your work should be viewed in the highly decontextual space of the white cube gallery or the kind of neutral, abstract space that is only possible in theory.

Your later exhibitions such as those at the Portikus and in the Gwangju Biennale were more or less marked by a more interpretive(?) intervention in placeness and spatiality. But I am a little curious about your more recent shows held outside conventional art spaces, such as a performance theater and a model home. Do I see an attitude of accepting multiple interactions with the meanings of placeness and spatiality? Or did you think that these sites were sufficiently decontextual because they have always already conveyed a surplus of meanings? Please tell me first about your choice of venue for the exhibition Apple vs. Banana—held in the model home built in the basement of the Hyundai Cultural Center.

Chung: Could you first explain what you mean by “multiple interactions with the meanings of the placeness and spatiality”?

Ms.C: It may be hard for me to answer that question, even though it’s me who said it. As you know, I have a split personality; so the one who is speaking now is different from the one who posed the question in the previous paragraph. (Laugh) Nevertheless, if I may roughly guess… wouldn’ it be something like the semantic domain of a work of art that is built in relation to or in the context of various aspects of a given space, such as special contexts, the space’s unique aura, sentiments, and so on?

Chung: I have never considered the model apartment at the Hyundai Cultural Center or the performance theater at the LIG Art Hall as the antipode of the neutral, abstract space. At times, it is just next door to the white cube. Those exhibitions can be understood as a case in which the narrative elements hidden in my work come to the surface. It could be true that my work is most powerful when presented as a “sculpture in a neutral space.” But I can have a sculptural exhibition in any space. Every space has inexplicable parts and all I have to do is to a produce a sculpture that discovers them. In the case of my solo show Apple vs. Banana, I was wondering how a sculpture could maintain a tense relationship with the context of the given space without losing its sense of presence in its narrative space. So I worked at the site—that is, in the model home—for months. The reason I felt I needed “what was made there” was that, because this abandoned model home was in itself a big object that shared similar characteristics with my works, I had to understand its interior structure, or, to put it another way, finely tune the relationship between the apartment’s interior space and my sculpture. Otherwise, my sculpture would have become part of the interior decoration or could have been placed awkwardly as an object that had nothing to do with the space. However, honestly, I think now that I should have investigated whether abstractness could emerge out of the concreteness of the space by making a sculpture that would gradually adjust the interior and exterior of the model home. If I had done so, the quality of “being long left abandoned” would have played an important part.

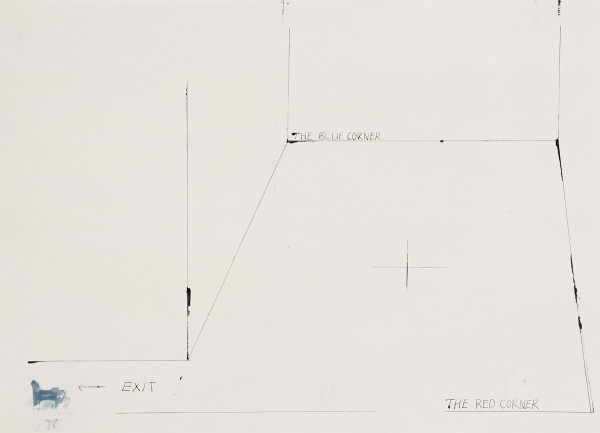

Ms.C: Is Monster Map, 15 min (2008) possibly a kind of allegory for the unique situation or context of the Gwangju Biennale?

Chung: No, it is not. It is true that Monster Map, 15 min was produced for the biennale, but it was not directed at any special situation or space related to the biennale.

Ms.C: In the 2008 Gwangju Biennale brochure, Okwui Enwezor describes your work as follows: “[Chung’s work] begins from an intense moment of reflection that is at once haptic and retinal, directed simultaneously at surface and what lies beneath. The artist achieves a vernacular of readily recognizable forms and materials by employing highly quotidian objects, for example, ice cream freezers composed of opaque glass and an upright goose cast in concrete. These objects are so well crafted that they take on the character of the uncanny. The disarticulation of such stable forms thus creates an environment of tension for the viewer, underscored by the phenomenological presence of the constructed objects, which are suggestive of minimalist sculpture.” It is rather difficult for me to understand how such concepts as “vernacular,” “uncanny,” “disarticulation,” and “phenomenological presence” operate in your work. I guess this was partly because Enwezor was summarizing his thoughts in only a few sentences. In any case, I wonder about your own opinion regarding his approach to your work.

Chung: I think those words express the mood of my work. But this kind of explanation, though convincing, makes the reader feel that she has nothing to say. It may shed light on my work in an attractive way, but aside from helping viewers to feel the “mood” of my work it can end up doing more harm than good to the discussion. Admittedly, it’s hard to explain my work with a few key words or in a few succinct sentences. Enwezor’s description was a practical choice for his critical situation. Even so, the phrase “the disarticulation of such stable forms thus creates an environment of tension for the viewer” is weighing on my mind. I am going to interpret it to my advantage: If the viewer does not get angry and just becomes tense when what she sees is inarticulate, and if this is because the shown form is stable, where does this “stability” come from? Does it come from the fact that the form is so well crafted? Is that all? I think that it is rather because the form determines its stance. Thus, the “disarticulation” could imply that object’s stance does not coincide with a majority’s understanding. If the viewer feels tense, we can also expect that she will be able to have a balanced relationship with the object’s stance.

Ms.C: As a matter of fact, Enwezor’s curatorial practice is deeply influenced by political-social considerations, in particular postcolonialism and global modernity. But it seems that Enwezor also made efforts to explain the aesthetic dimension of your work because he himself is a curator who never depreciates the importance of the aesthetic. Indeed, when he emphasized “the politics of form” as an axis of the 2008 Gwangju Biennale, he referred to you as a representative artist concerned with this subject. Looking back, Korean art scene was for many years divided into two camps—those dedicated to aesthetics versus those with political concerns—and it is only recently that artists can more freely explore various arenas of politics by striking the balance between aesthetics and politics. But with the recent rise in political art witnessed in Korea, it is common that art works don’t receive much critical attention unless they bring up sociopolitical issues or become themselves discursive examples or references for the issues. Such being the case, works dealing with form are easily dismissed as conservative or classified as having an aesthetic attitude that is considered incomprehensible. In this way, they end up occupying an unstable position in the art scene.

The truth is that in Korea and some of other Asian countries, works that have a more rigorous and precise attitude toward form have trouble establishing themselves. The interest not only of the public, but also of the market, is directed mostly toward works that pursue exaggerated spectacles, attach weight to handicraft decorativeness or finish, and make use of flamboyant visual effects in a one-dimensional sense. Excessive obsession with plasticity has been pushed far past the genuine politics of form. In this context, I think it was significant that Okwui Enwezor cited a group of Korean artists invited to the Gwangju Biennale, including you, as producing the politics of form. The curatorial team also heavily considered politics in the research and selection process. Hence my question: if your work is discussed in terms of the politics of form, what do you think “politics” implies?

Chung: The politics of form implies a state in which an aesthetic choice naturally has a political dimension without touching directly on political issues, or in which the process of creating form becomes itself political. However, I wondered about why we came to need there to be a relationship between form and politics. The relationship between politics and art may be as awful as that between politicians and art, or between artists and politics; on the contrary, it can be connected with the strictly critical function of art. This critical function is sometimes aimed at social and political issues and other times performed through all activities in the world on microscopic to macroscopic levels. We sometimes need to think about this: what on earth do we devote ourselves to and why? If contemporary art devotes itself to “politics,” it may be because it is necessary to summon the strictly critical function particular to art (the necessity may seem natural now when looking around our present world, but on second thought, it may have always existed in all times and all places, regardless of whether or not art remembered it). Or it could be that contemporary art, degraded to an inferior position because of the world’s imbalance, found the reason for its social existence through politics. Anyway, isn’t it the case that politics refers to so-called relationship with power? Is it still believed that aesthectic choice is the oldest quality and power of art and inevitably has the function of self-examination and the power of sharp spirit? Can aesthetic choice change politics with the function and the power?

Come to think of it, form must be an exceedingly inferior and quite inconvenient medium, for it is not a direct language nor does it communicate quickly. It circulates like a special object closely connected to money, accompanied by the primitive body of matter. Though I cannot define clearly what role form plays in its relationship with politics, I can say at least that the role has something to do with thinking critically about the scope and process by which politics transforms and reappears in the context of society.

Basically, I do not agree that art should focus on a politics based on ethics and practice. I would like to re-emphasize the fact that art should deny all kinds of constraints, including those of ethics and practice.

Ms.C: For the last four years practical politics and present social problems have certainly introduced a sense of urgency to the Korean art scene. But this period was marked largely by excessive reactions and accusations and the overuse and misuse of participation. Too often criticism is directed outward and not inward. Some artists intentionally display their ethicalness and intelligence, while others indiscreetly take terms and content from the domain of discourse and philosophy and put them before their work out of their sheer desire to dominate the scene. Witnessing all of this is terribly confusing. Isn’t art allowed to inspect any matter in any field, including philosophy? And should a work of art prove that fact for itself?

Chung: In any case, I don’t think that art is an instrument of judgment. I only wish that ethics and intelligence would not be mixed with vanity.

Ms.C: Most people may not remember this, but you were once a member of Forum A. It was a journal published by Alternative Space Pool and was known for taking a materialistic stand. Your participation in this magazine was interesting in that it demonstrated your interest in political engagement, though you have distanced yourself from those activities since. I wonder what you gained from that experience. Though I myself do not agree that an artist’s art and her personal engagements should be considered side by side, your relationship with Forum A suggests that there is a kind of rupture in your trajectory as an artist. You may have found conflicts between the journal and your artistic pursuit. What made you participate in Forum A at that time, and in what activities were you involved?

Chung: I participated in Forum A because I was interested in the activity of art and a sense of ethical responsibility. To be sure, I found my work rather estranged from what was going on at Forum A, but I was more interested in what was missing in me as an artist. I seemed to be lacking something because, out of all of the things that comprise the activity of art, I had not taken much interest in anything other than the work of art itself. In those days, the Forum A group sought to establish a discrete language of art in the Korean context. At that time, all kinds of currents were indiscriminately running through the Korean art scene and I thought we needed more solidarity. The projects I worked on at Forum A with my fellow artists and critics in the late 1990s stimulated my interest in the structure of art, a topic of discussion that had previously been absent in the Korean art scene. But, because the members were not open enough, we nevertheless just went around in circles. Finally, after my last project—which was coordinating the workshop Community and Art with Yongsuk Jeon by inviting alternative spaces from various countries—I began to distance myself from these activities. I not only found it very exhausting to play a supporting role in projects not closely related to the heart of my work, but I also found it hard to feel a sense of solidarity with the group any more. However, the workshop that had taken so much planning and preparation offered the participating young artists an opportunity to grow, and I think that, paradoxically, the experiences with Forum A inspired me to have a more open and independent attitude about art.

Ms.C: Let’s think again about politics in term of form—I’m curious what a “politics of form” looks like in reality. As I see it, your politics of form means something like a way of exact thinking on, and serious deliberation of, decisions in every moment. I believe this is where politics really comes in. How can you explain the core of your thinking that dominates every moment related to decisions about form?

Chung: Well, I’d rather say it concisely. If my sculpture is the form obtained in the process of finely tuning the social conditions and relationships of objects, the question that dominates this process is “so, did you find all the differences?”

Ms.C: Let’s talk about your recent work. Your Monster Map, 15 min that first began in 2008 has expanded to use a wide variety of media such as drawing, installation, performance, and so on. In fact, the concept for this interviewer—a single person embodying the voices of eight different people—was appropriated from your Monster Map. That piece, though it has moved through different media and genres, seems to continue to be self-referential. Has Monster Map actually expanded and grown over the years, or is it merely repeated in different renditions?

Chung: Actually, several of my earlier works are also related to ghosts: Monster Map, 15 min.: Ghost, Fire, Waves (1998), Ghosts Will be Better (1998/2005), and a series of carbon paper drawings from 1998 to 2000. In these drawings, I dealt with the perception of ghosts through the transformation of objects or through typical ways of expressing ghosts, and tried to bring in humor by drawing ghosts in place of the female dancers in Matisse’s painting The Dance. It was only later that I realized this long fascination with ghosts led to Monster Map, 15 min. (While I was working on Monster Map, 15 min, those earlier works never crossed my mind.) Monster Map, 15 min multiplied and divided in many ways, continuing to offer motivation for my later works. My later works, nevertheless, have their own originality that does not belong to Monster Map, 15 min; in this sense, I think it is not the case that the piece has grown, but that it has made my work in general grow. This is why I have recently been receiving frequent questions about these works from curators, and why these works are likewise frequently referenced.

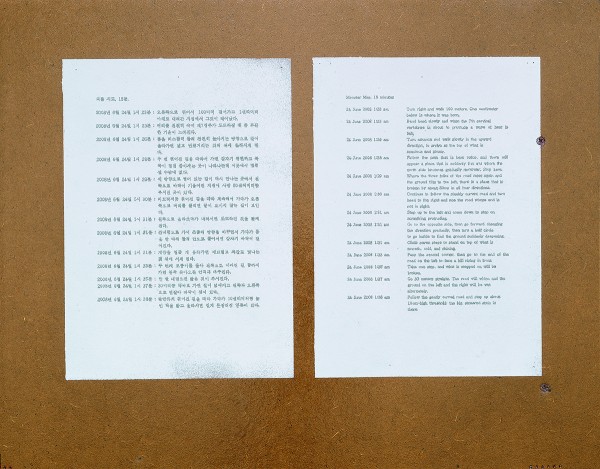

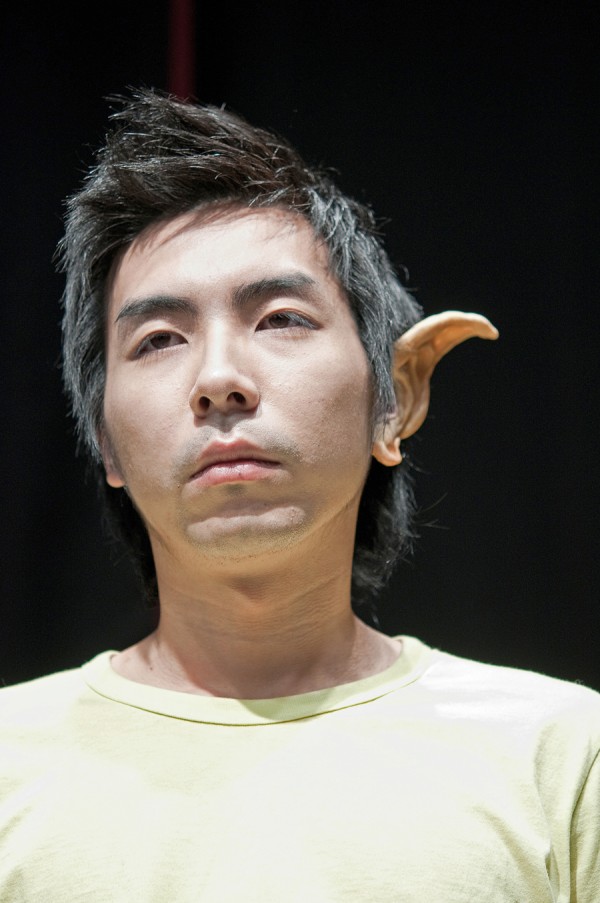

Ms.C: Monster Map, 15 min was for me a kind of prose poem of the absurd. Therefore, when I heard about the piece The Adventure of Mr. Kim and Mr. Lee that had developed from it, I thought that the performance would be a very melancholic monologue, even though it is directed like a situation play. At the end, the work was like an existentialist play, which satires a relationship that fails to be a relationship or an over-relationship that is not actually a relationship. Thus, I was anxious that the performance would become rather idealistic, or get so speculative and distinctively dystopian as to fall flat. And after seeing it, I found that my expectations had been partly right and partly wrong. Before I tell you my impression of the performance, I want to ask you about how you, as the author of the play, felt seeing the performance being acted out.

Chung: When I was reading again the discontinuous dialogue between two persons written in my drawing for Monster Map, 15 min, the first idea I had was to produce a piece consisting of as many small performances as the number of the performers, in this case 9, by having each of them spend the running time in his or her own way. Though this plan may have been idealistic and terribly uncontrollable, it was my intention to deal with discontinuous time, the beginning and end of which would not be distinguished. The actors were all non-professionals except for one person, and I practiced with each of them. They would sit motionless for quite a while, their face and body muscles subtly changing and collapsing from fatigue. Watching them doing that, I thought to myself that this might be a performance that only I would watch to the end.

Ms.C: In my opinion, the performance was a good way to capture and develop something from the temporality and spatiality embedded in the original drawing Monster Map, 15min. Still, I asked myself whether it was really necessary to send human actors out onto the stage like sculptures simply because it was being played in a performance hall. Indeed, the space of your work used to be occupied by the tension among objects and their dialogues, which are marked by an extremely abstract but concrete visuality. Since your sculpture is exceptional in the Korean art scene for its linguistic performativity, I think that your sculptures—with a language stronger than that of any actor—should have taken the place of actors. I’d like to ask if you chose to use actors as a way of compromising with the genre of performing arts.

Chung: Frankly speaking, the preliminary plan proposed at the initial stage was to hold a contemporary art exhibition in a small theater, and I actually meant to display my sculptural works. Besides myself, some other artists were also invited to participate. An option was to install sculptures standing stately on the stage of a small theater, inserted here and there in the seats, and so on. For various practical reasons, however, the show turned out to be a solo show of my work and, on top of that, I was given a bigger theater space. Well, this may sound a little pathetic, but we couldn’t prepare a sculptural exhibition suitable for the scale of the LIG Art Hall, that is, with such sculptures as you described. However, admitting that a performance by performers was a practical choice, I wouldn’t call it a compromise. It was the second-best alternative indeed, but a pretty positive choice. In the small theater, I would have liked to comfortably reveal the space and experiment with sculptural presence since the theater itself had a light spatiality. For example, interestingly, a sculpture on the small stage was likely to make anyone in the seats near the stage (even the last row of seats is not far from the stage) shout at the sculpture to move. But since the LIG Art Hall was a truly commanding and solid space I thought there would be no difference between how one would walk around sculptures on the stage and in the exhibition space. In other words, it seemed like it would be hard to change the temporal experience of viewing the sculptures. So I decided to present a performance fit for the given performance hall. It was not that I replaced sculptures with human beings; I exchanged the places of actors and the audience (the actors stood still and the audience walked around) and transformed the typical usage of the theater space (the audience’s path of movement was extended and changed, and whereas an audience normally experiences time communally, here they experienced it individually). Even if in the end the piece seemed to consist of human sculptures, the problem would be in the directing—not in the fact that the actors were not real sculptures. Or, I’d like to rephrase the question like this: was the problem really that I treated human beings as sculptures, or that such a staging was essentially unimpressive…?

Ms.C: It doesn’t matter in the least that you treated humans as sculptures. The only problem seems to be that, though you undoubtedly made a significant attempt, the performers and their presence on and possession of the stage were relatively weaker than the previous performances of your sculptures in exhibition spaces. This may be because the performers’ body language was neutralized when it met your sculptural approach.

Chung: I completely agree that “the language created by performer’s body was neutralized by my sculptural approach.” To all appearances, body language involves movement. Or maybe there needed to have been an audience that could stand the boredom so terribly well as to watch faces, body muscles, postures that were changing at an imperceivably slow speed. I may have created a rather strange documentary (about the body).

Ms.C: Some time ago, I heard one of my fellow curators saying this: “I cannot make out what Seoyoung Chung’s work is all about. Normally, as a curator I don’t like works beyond my comprehension. But strangely enough, I find Chung’s work attractive. It’s a curious thing, indeed.”

Chung: (Laughter) Hearing that, I feel as if my work really has class.

Ms.C: As a matter of fact, it seems rather embarrassing that a curator likes a certain artist’s work but cannot understand it at all. Nevertheless, this in some respects seems to epitomize how your work is received by those in the Korean art scene. In other words, it could mean that though they fail to articulate their thoughts about your sculpture, they recognize its presence or some special quality, to say the least of it. To be frank, this also seems like a problem and you must have heard this kind of response for a long time in Korea.

Chung: They don’t know what my work is about but they like it; that sounds positive to me because it means that they can enjoy my work without grasping it with pre-formulated ideas or emotions. But this also means that they do not go beyond the work’s atmosphere to consume its very presence or special qualities.

Ms.C: I agree with you. I often say that novels and literature are very different. Novels can be a matter of the reader’s enjoyment, but literature requires more than that. Similarly, I think there is also a difference that allows one to distinguish, among thousands of works, between novels and literature. The problem is that your work, which should be considered on the level of literature, not of novels, is hard to approach. It all the more requires one to contemplate its language and think critically. However, in Korean critics’ circles, it is still hard to find critical works that support your work and bring it into focus. This could be why the Korean art world in general does nothing more than generally consume the atmosphere of your work. In this sense, I am expecting that this dialogue between you and the eight different voices in me will contribute to clearing away the haze enveloping your work.

Now, let me ask you about the “audience,” that element that is too obvious and almost always mentioned but nevertheless very complicated and difficult for all. The existence of the audience inevitably becomes a key element in an exhibition, or a channel through which an artist presents her works. Are you interested in how your works are received by the audience, the audience being the indispensable element that supports the art world but stands outside of it? Please tell me if you have any special memories of the audience’s response or your experiences with them.

Chung: I do not carefully watch general audiences. To speak frankly, I feel ill at ease with them. I always have a hard time with social communication and often forget the audience—perhaps because they are unspecified multitudes. Of course this is in no way intentional. I do not know how many non-art people go to see contemporary art in Korea these days, but I think works of art should be widely shown in any case. The reason I continue doing this, regardless of whether I succeed in communication, is not only because the attention art gets from the public is important, but also because it is only after sending her works out in this way that an artist can also be released from them.

Ms.C: By making the audience’s response a part of your work, it seems that one of the key “outcome” of your work is its “unexpectedness.” If unexpectedness is the opposite of “common sense,” can the creation of unexpectedness through art help produce cracks in society’s generally accepted ideas? Do you think there is still hope in art to which we can cling? If so, how do you think art can contribute to both the human race and society?

Chung: The point lies not in using unexpectedness as a main instrument, but in the fact that art by nature causes cracks in generally accepted ideas. The fact that art still exists in this world already contributes to producing these cracks. However, I find it very dull that only a few contemporary artists can perceive the seriousness of unexpectedness in everyday life, and it makes me uncomfortable that it takes them such a long time to do that. Art will demonstrate its presence if artists don’t attempt to take power as the majority or give up conflicts to advance time. I think that even though contemporary art is in a disadvantageous position, it is an interesting and fine genre because it never stops paying attention to all the problems of the world. In this sense, art is already contributing to humans and society.

Ms.C: This has been a serious and interesting conversation. Thank you very much for your efforts to give answers to the schizophrenic questions posed by multiple voices in me. Finally, I’d like to ask about your present concerns. Can you say that these concerns are absorbed or reflected (certainly in a roundabout way) in your recent or ongoing work?

Chung: My present concern is that the things an individual is willing, and able, to deal with in this world are rapidly decreasing in number. My struggle with this issue naturally has a strong influence on my work.

- Ms.C is an imaginary interviewer whose questions were drawn based on the cooperation of eight critics and curators including Sugi Kim, Jangun Kim, Inhye Kim, Hyunjin Kim, Heejin Kim, Youngmin Moon, Soyeon Ahn, and Youngjun Lee. This interview format—in which multiple voices are presented through one body—was proposed by Hyunjin Kim, who was inspired by Seoyoung Chung’s Monster Map. Ms.C, who is composed of incoherent voices or voices from various positions, epitomizes Seoul’s art scene.