Interview: Chung Seoyoung

Your titles are as bizarre as much as your oeuvre so that they shock the viewer, yet they are refreshing: Apple vs. Banana; Leave the Campfire There; On Top of the Table, Please Use Ordinary Nails with Small Head. Do Not Use Screws; Monster Map, 15 min.; etc. In a past interview, you’ve mentioned: “I hope my works represent an attitude of originality while having a linguistic congruence in attitude with the work on display,” and I’m curious to find out if there is a set standard, or a method that you have for entitling them.

Two things: one is to make titles as I see them. Say, if the work is a tower, it’ll be called Tower, if it’s a stain, then it’ll be Stain. There’s no extra thinking involved, and I call them as I see what they are. The other way, is maybe to find out if it has “the same cells and tissues,” although the words or phrases do not direct to anything. And other ways of entitling include, although they may not directly represent the work or anything, following the psychological backgrounds or experiences that I had when creating the works. The experiences may include things like. things I thought about, thing that have influenced me, things that made me mad because I couldn’t resolve right away due to technical problems, or things that I found pleasing because I had done something well. Among them, I find the words or phrases that have the same matter and aren’t confined, and thus use them as the titles.

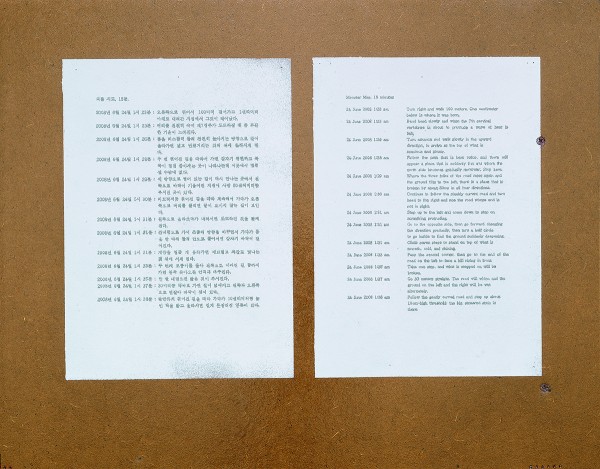

The text on the wall in this exhibition comes as a sort of a declaration. The tone of the text is quite commanding, and while reading it aloud and acting accordingly, I suddenly find myself wondering why it is directing me to do so. There aren’t any correlating narratives, either. But, it seems to possess certain elements of subtle chuckle. Before this, there was the dialogue(The Adventure of Mr. Kim and Mr. Lee), and a diary (Monster Map, 15 min.), in the form of texts. What do these texts mean in tour work?

First of all, the text is a work, not a declaration. The text, which is more of a technical instruction, is a humorous, yet a serious personal statement about the inception of my work which engages both time and space. How and when my sculptures come to form is a bit more complicated; however, I wanted to simplify them and write it out methodologically. For example, the ‘beginning’, or bringing together two sets of chairs and desks, is a sort of a prerequisite. It’s just like saying at the outset: “let’s say there are two apples here.” Or, “let’s say there are a woman and a man here.” This might be of course just a prerequisite for me to ease into the following actions, or it could be the beginning of an arduous adventure. But, despite all that, while at it, it designates a particular someone and requests to give that someone a call. There’s absolutely no guarantee that anything would happen, but things start to gain more density. Situations and connections arise; tension and energy develop as I select the words and phrases. Thus, motif for behavior is created, leading to the setting of a particular time and space.

It is as if I’m trying to handle a specific form or a situation or just irresponsibly expressing them, because I sometimes become too sensitives as I want to make accurate decisions.

Looking at The Time is Now and Problem That Cannot Be Separated 2, which are to be included in the exhibition, it feels like I can now begin to understand the work There Is Nothing Left to Add nor Take Away (2008), form the Apple vs. Banana exhibition. Tight tension and delicate balance that cannot be “added or taken away” can be observed here, and comparing them to other works before, in what aspects are they different or similar?

The Time is Now is a work that fills in fine imbalances that are brought about by a beginning - placing a desk on a pedestal - without any directives. It’s quite possible that it may never end because it needs constant balancing: a continuous proliferation of illogic that began from a sloppy beginning. The point of this work is to set a prerequisite, and balancing out the gaps which are made meanwhile activating the prerequisite. That is the basic principle of mechanizing this sculpture. In Problem That Cannot Be Separated 2, the broken sticks turn little by little because of their angles, continuing their infinite extension. These two works, compared to my others, are based more on common sense.

Let’s go on to another subject about your work: some of your presentations, while they include everyday objects, seem to defamiliarize and give off bizarre impressions. It seems there is a consistent attitude and ambiance.

The reason why my works evoke poetry, absurdity, and bizarreness is probably because of the ambiance aroused from the methods I’ve been taking from my point of interests. It’s certainly something that is tangible and exists as real, but unfathomable, namely, not because it is mysterious or unrevealing; but too complex, exaggerated, illogical or extremely deceptive, or forgotten, repressed; my work itself is a process to cope with, and understand the questions against the silence of the unknown. The poetic element, in addition, is probably derived from the ‘poetic accuracy’ needed to withstand the weight of the silence.

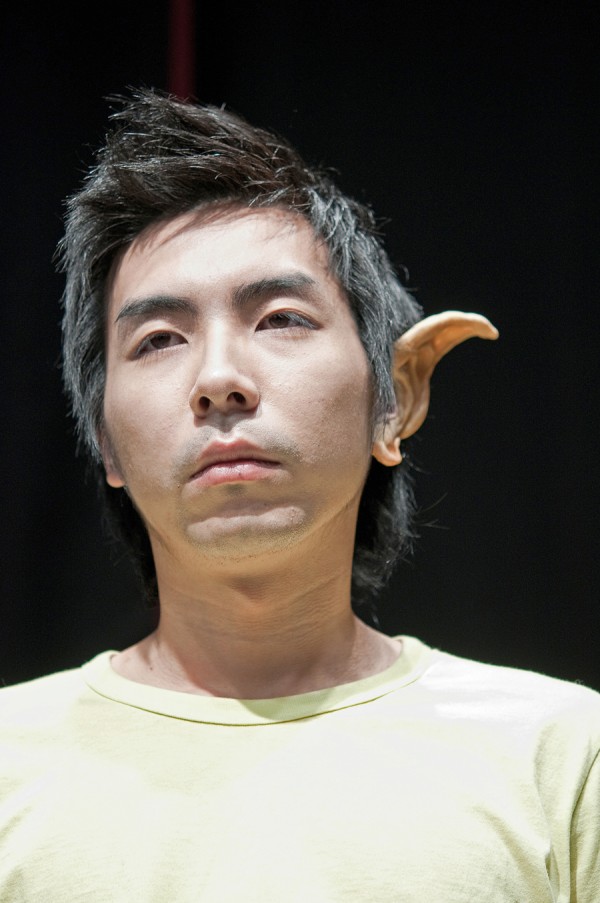

If you were able to find any consistency within my oeuvre, that is probably because it’s the constitution of being an artist. Fundamentally, an artist is a person who constantly feels the presence of the “things that yet exist,” as well as a being with special organs that ceaselessly search for that and actualize in reality. As an artist myself, I tried my best to gratify to such physiological constitution, trying hard not to lose grip. Recently, I’ve been reading a compilation called A Letter from the Sea by the novelist In-Hoon Choi. The unusual, elegant tone of Choi’s Korean writing speaks in depth about some extremely difficult issues of art, which makes me recommend the book to others. It allowed me (the idiot that I am) to bring up things that I couldn’t understand or put to language before reading the book. One of the most impressive quote from the book, “(things) that is real to those who understand them; nonexistent to those who do not,” is a statement not only about art, but also about thought, literature, and ultimately, the limits of life.

Before, in another interview, I mentioned about a dream I had before. I was aware of being in the dream, and in that dream I felt something very strange, but I couldn’t quit make out what it was. It was definitely something very powerful, as if it was real, and I was able to remember the feeling very clearly even after I was conscious. It was as existence that cannot be formalized but powerful. I believe I had such a dream because at the time I was struggling with questions and limitations. And I think it is Choi’s book that would enable me to describe these feelings into words. Because artists are such pitiful beings who invest their efforts to produce forms that never existed, I too, have extremely loyal to such effort -because I’m an artist. If you ever found any consistency in my work, it’s probably because of this attitude.

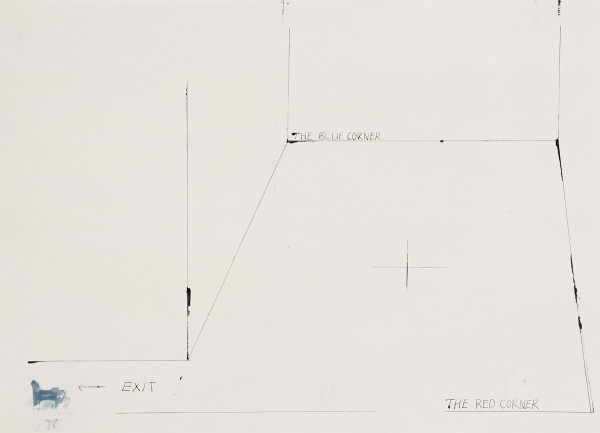

Your works suggest the importance of space as much as the works themselves. I’m curious to know how you mediate the balance between your work and the space, as you must do so before you begin.

My works ultimately is presented in a form of some object, therefore space becomes a crucial factor. The works are not some sort of hologram that floats in the air; rather, it’s an actuality that exists and exhibits in real space, leaving no choice for us to consider all corresponding connections that arise between them. Thus, I keep thinking about what others view as ‘without differences’ and call ‘the same’, meanwhile ceaselessly bringing up the unrecognized, wasted differences.

I spend a lot of time on the space when I prepare my exhibitions, but there isn’t a set manual. I encounter new spaces every time, and new concept and design are always needed. In other words, I think about the physicality, shape and form, size of the space, and about the people who would enter that space. I also try to read my own reactions to the space. I try not to immerse into the space, namely, place my works not to harmonize with its surroundings. The structure and process of my works do not aim for a comfortable viewing experience. Conflicts arise here and there as I experience the space, which is a process very similar to how I create. I tend to think about how I could stir up conflict in a stable space. I deliberately pick up on problematic elements, try to solve them, discovering the vitality of the space. Some events are going to happen in the space, and events naturally lead to conflict; therefore I try to utilize the space to amusingly, or earnestly reveal the conflicts. Then, I’m carefully adjust where a piece of work would be placed, as a single milimeter deviation would be the difference between conflict and stability.