Chung Seoyoung

Ahn Sohyun: For this exhibition, you submitted a work entitled Snowball, comprised of two white spheres, each with a diameter of one meter. At first glance, the piece seems to imitate snowballs; on closer investigation, however, it appears to distance itself from mere representation. I would like to know why you chose to exhibit this particular work in the show.

Chung Seoyoung: I tried to make the two objects look like snowballs, imagining rolling spheres of snow inside a bounded space. I know of an artist who placed a real snowball inside a container and documented the entire melting process. However, my work more closely resembles that of an artist who made several snowballs to sell, as my interest was focused less on nature itself.

I believe that ‘landscape’, as part of nature, is integrally related to the human experience of time and space. As such, ‘(Im)Possible Landscape’ refers to the wide range of forms and shapes that landscape can take. I considered the work Snowball to be appropriate for the exhibition, therefore, as it reflects the various, shifting relationships between different dimensions of nature.

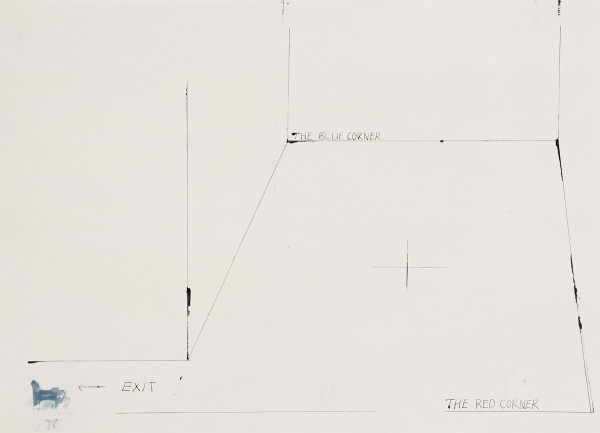

Ahn: Monster Map, 15 min is a record of fifteen minutes spent wandering by a being who was born on June 24, 2008 at 1:23 am. The seven back alleys are more like a maze than a friendly ‘map’. Is it possible to regard ‘(Im)Possible Landscape’ and ‘Monster Map’ as synonyms?

Chung: Monster Map, 15 min began with an idea about humankind’s special ability to actualize something unreal. Historically, our fear of the world around us led us to create stories about monsters, which then proliferated organically. This work is a monster’s map without any visible monsters. It does not seek to state or clarify something; rather, it is about the feeling of being surrounded by the unknown — moving out of the familiar world and then slowly returning to it. And I think this is where you find a similarity between the two terms.

Ahn: Your works have paradoxical titles, which play an important role in constructing their meaning. They do not connect objects and languages intimately; on the contrary, they serve to trap viewer in a state of silence and darkness, enabling him or her to concentrate on the reality. What are you trying to convey in the titles of your work?

Chung: I think contemporary art has dealt carefully with the issue of perception. This is also the issue I am most anxious to explore. The titles I give to my work and exhibitions are selected to open up the fertile meaning of perception. At times, the ability to perceive seems to be lost, as words and images do not match. The words I place next to my works are not intended to describe, symbolize or provide any kind of metaphorical framework for the content of the works. In fact, the titles I choose are another type of work in themselves, using language to shape the lineaments of a piece, or to gesture beyond the boundaries of that piece to where it might lead. They reveal thoughts attained after the work’s completion. I suppose that the titles of my works all point in different directions.