Interview

Sung Won KIM: Let’s begin by assuming that for an artist, an exhibition is an opportunity to communicate his or her work to a multitude of random viewers. In this regard, what were the important elements that informed your preparation for the exhibition at Atelier Hermès? Also, what was the most important for you when you were preparing the 2005 exhibition at Portikus, Frankfurt?

CHUNG Seoyoung: The process of preparing the two exhibitions you mentioned was fun for me as it turned into a situation drama in each case; my thoughts materialized into objects, and the objects thus created induced movements. Each story was independent, yet in the end they came to have a particular point of view as a whole. I enjoyed the tension inherent in this process. As for the assumption of the communication… A thought that ricochets out of anybody is clearly directed toward the world. I wondered about whereabouts of the world I understand, where it might be moving about. I hope it is a place without fear.

Sung Won KIM: Time and again, the objects you choose exist in a particular situation, and their forms of existence are borrowed from the everyday. Your current exhibition at Atelier Hermès is a collection of individual objects, but at the same time how these individuals comprise a whole seems to be an important issue, too. Looking at the objects individually, it is difficult to find any apparent connection among them. Of course I am not referring the forms here. Regardless of their disparate visual exteriors, it seems that the objects are linked to each other in a more essential way. How did you want the connection to be conveyed to the viewer?

CHUNG Seoyoung: It seems that I have already answered this question in my comments on the Portikus exhibition above. When we look around, everyday life is surrounded by forms that, with very little or no change to them, could be made into wholly new phenomena. The “essential link” you mention perhaps comes from the fact that I’m always looking for this–what I call–‘piggyback’ phenomena; that they are not limited to any special forms; that they can be found anywhere and everywhere. I don’t know if it can be conveyed in any particular way.

Sung Won KIM: The titles of your exhibition, and their connection to the respective exhibitions, have been quite extraordinary. For the current show, your title is On top of the table, please use ordinary nails with small head. Do not use screws and for the exhibition at Portikus the title was Leave the campfire there. These titles, and how they related to the exhibitions, are not at all helpful to viewers in understanding the works. In your exhibitions, what role do titles play?

CHUNG Seoyoung: “On top of the table…” is from an actual instruction note. I found the note quite by accident, and it was for a carpenter at a museum where I had an exhibition some time ago. For this title, I changed a line from the instruction. I felt the manner and the tone of the note suited me well. Leave the campfire there is about a way to deal in a simple manner what is impossible to deal with. It echoes with the joke, “How do you get an elephant into a refrigerator?” The answer is, “Put the elephant into the refrigerator and close the door.” It is not easy to come up with show titles. What I strive for in a title is that it be original–like any other work of art. At the same time, it has to have a linguistic congruence in attitude with the work on display.

Sung Won KIM: There are artists who would say that answers to the following questions are not essential for communication between their work and the audience: Why did you choose the particular objects you did? Why did you make them? What do your artworks mean? Would you take the same position? On the other hand, your works convey a strong message of artistic position, but at the same time you seem to refuse to give any interpretation or explanation. This is not an issue about whether or not art should serve a specific purpose. For example, in the case of Stain and Table that are included in the current exhibition, how does the viewers’ knowledge of why and how the idea originated contribute to their appreciation of the works? Or, on the contrary, would it interfere with the free imagination of the viewers?

CHUNG Seoyoung: I want to value the fact that there is passionate support for the existence of artistic language. For Stain or Table, I enjoy remembering and sharing the stories of where the ideas first came from. The emotions, the suppositions, the misunderstandings, and the discoveries generated from the advent of a particular phenomenon are fascinating, and I can talk about them. However, if someone asks me to explain the meaning of the phenomenon, all I can do is say “The meaning is in front of you to see.”

Sung Won KIM: The titles of your work have very specific references, as in the case of Gatehouse, for example. In this case, from the viewers’ point of view, if it were not for the rather metaphoric title, they would not necessarily associate it with a gatehouse. On the other hand, in the case of A Goose, a work in the current exhibition, anybody could tell that it’s a goose. The viewer in this case would get flustered. The kindness of the title notwithstanding, the viewer becomes all the more uncomfortable…

CHUNG Seoyoung: Hmm… Why the discomfort? I needed a goose, an animal that is needlessly noisy, that has proud buttocks but is actually quite dumb. I wanted the advent of such a goose, and as my departing point I wanted an animal that is neither more nor less than that. So what else could I call it but ‘a goose’? I do sincerely hope the discomfort is not necessarily translated as displeasure.

Sung Won KIM: Let’s talk about sculpture. I do not want to categorize your work methodologically. Still, you are clearly fond of sculpture as a tool of visualization. The choice of materials, the precision of the method, and the finesse of the form are the important characteristics of your work–even if we grant that your work does not necessarily represent a sculptural tradition. Keeping in mind the ultimate purpose of your work, how would you explain the relationship between your work and the language of sculpture?

CHUNG Seoyoung: Materially, a thing-ness, defines my work. An object is a material being that is clear and specific. In my work, this specificity is coupled with ambiguity, thus creating a tension. The sculpture stays exactly where it stands; it is you that is pulled toward it.

Sung Won KIM: Do you draw first prior to making a sculpture? What is the process? How does a drawing come about?

CHUNG Seoyoung: If I have a clear object in my mind, then the drawing is no more than a memo or a plan. Actually, in the past several years I have not drawn much. I did a lot of that until about 2000, and since then I have done it occasionally, here and there. I did a lot of drawings on carbon paper around 2000. Some of them were comments on the works I’ve already completed, and others were recordings of the details of the objects that came up in my mind for the first time. From the period after that, I have a few, a very few, drawings in which I tried to draw humans, which have yet to appear in any of my work.

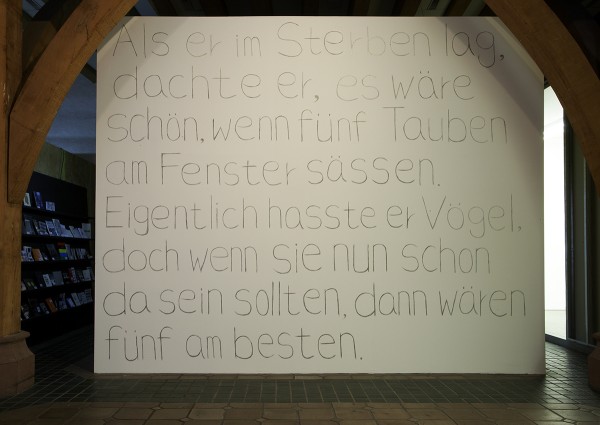

Sung Won KIM: What prompts you to do surface works–drawings, paintings, texts, and wall drawings? At the Portikus exhibition you had, along with sculptural pieces, a text piece. It was, When he was lying on his back, facing death, he thought that he would like to have five pigeons by the window. He doesn’t actually like birds, but he thought that if a bird has to be there at all, then he would like five. You also showed a carbon paper drawing called Wow in that exhibition. Do these works have any special meaning for you?

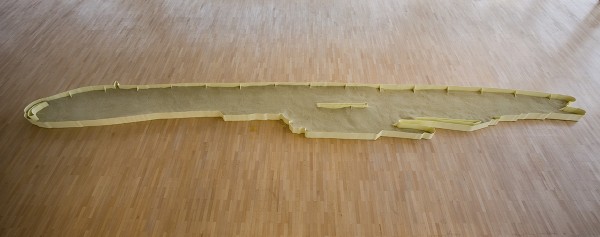

CHUNG Seoyoung: When a story is too burdensome for an object to carry because of its size, a drawing takes over. In the case of When he was lying on his back… I originally had it written on a small carbon paper. It was then expanded to fill the large wall at Portikus. The drawing [of the text] occupied a huge space on the wall, but reading it erased the weight of the expansiveness of the physical space. Wow is also from a small carbon paper drawing. I drew on the wall directly from the copy of the drawing. The white painting on the floor below the drawing was added for the exhibition. The drawing floated about slowly, and in tiny movements, creating an atmosphere of ignoring the obvious presence of the sculptures in the space.

Sung Won KIM: Your works are mostly created as a result of the process of “association”. The association in your case takes place under “the condition where imagination and fascination have been added to text,” or in “the process of eliminating what already exists or the structure that is already given.” For example, The Things That One Must Get Rid of At Least Once a Year, From Noon to Midnight, and An Ice-cream Refrigerator, a Cake Refrigerator are results of associations that started from simple and ordinary occurrences. Do you expect the viewers to be aware of your associations? Of course, the more the viewers uncover your associations, the more the abundance of their free association would be interfered.

CHUNG Seoyoung: It seems that knowing my “association mechanism” does not necessarily lead to uncovering of my work. The knowledge can function as a silhouette of the work. There is no manual. Why would anybody want the boredom of uncovering every detail of the origin of the work? Wouldn’t it be more fun to go forward with the reality–the work– in front of one’s eyes?

Sung Won KIM: You have said once in reference to your work that it is “an exercise in going back and forth between what is unrealistic and ordinary, and between what is very abstract and very specific.” At times such an exercise shows us what is invisible, and at other times it hides from us what is visible. On the other hand, this process also brings obstruction and confusion to our normal way of thinking. Also, the exercise has enough references to reality that we can recognize, and therefore it seems familiar to us; and yet when we trace these references in ways that are familiar to us, your works become strange to us.

CHUNG Seoyoung: The world I understand is bewildering. It makes one feel what is not there. One way for me to endure this painful communication is to show what it looks like and to spend the time together with the viewers.

Sung Won KIM: Lastly, let’s return for a moment to the time when you were a student. You studied sculpture in Korea and went to Germany for graduate work. How do sculpture and the study abroad influence your work?

CHUNG Seoyoung: Sculpture made me think about how objects–things–become sensitive, and in Germany I thought about it even harder.