Hating “Depth”: Reverse Perspective in the Work of Chung Seoyoung (summary)

“I can’t stand ‘Depth’,” she repeated to me during our discussion. Her work begins with a reflection on things that have been pushed to the edges of “deep” perspective. She is disgusted with the vanishing point, with the authority of emotional depth. By bringing Depth to the surface, she uncovers the superficial. Chung Seoyoung’s work extricates itself from authoritative perspective, from the mapped-out earth of a Borges fable, or from Baudrillard’s earth swallowed up by a map. Instead, her work redesigns a forever-unfinished map in which many roads are mapped out, many places from entangled agglomerations, and many ambiguous objects suddenly appear to tell a story.

I. Eyes.

The blind hero of a movie recovers his eyesight and plunges into confusion. Once he lived with antennae, and now recovered sight becomes a mixed blessing. Another operation on his eyes proves to be a failure, and he falls back into blindness and his old habits. In art, the visual domination that is so powerful it could be called “oculocentrism” came to a climax with the invention of perspective. By dismissing all sensation but the visual, perspective exacted the sole worship of light that made the visual and spatial depth that cuts across it and that the spectator sees as the real world. Chung’s work is a strong objection against visual domination. Her car etched on glass is like a takeoff on Duchamp’s Glider Containing a Water Mill(1913-1915), or a parody of the flat canvas on which an illusion of depth is created. Her car, wandering between visual depth and palpable flatness, reminds us that her tableau is a flat object that belongs to daily life.

Chung collects the discarded objects of visual domination: a breath or a touch of the hand in darkness, “things” that the atmosphere of Leonardo da Vinci saved from the perspective of Alberti. While Leonardo described dust-filled air and vapor, Chung wanders among them. Instead of observing things from afar with her feet on the ground, she throws herself into space, where objects thrive, and extends her hands to touch them, then leaves them in an ambiguous state while feeling their surface. By rescuing the object from vision’s categorically decisive scalpel, she protects her vital ambiguity.

Her works are tactile landscapes freed from the hierarchical visual distance between object and subject. Object and drawn object negotiate with each other. Drawing escapes from visual domination. A skyscraper and a mountain are side by side, a lookout is as small as a table; a lamppost multiplies and floats, flowers and cacti punctuate a landscape but no longer obey nature’s size restraints. Two columns are drawn with perfect one-point perspective. Contradictions grow. A flower is bigger than the lookout, the lookout is bigger than the Eiffel Tower and the panorama. All of these objects escape the dragnet of perspective. And when perspective collapses, time also collapses. Chung ignores traditional creative process, progressing from drawing to real objects. To create Lookout, first she made a real postcard photo of it, then she drew it. She created flowers and cacti with Styrofoam in a to and fro between drawing and sculpture. Each image is a provocative confusion of fragments, what Jameson calls a schizophrenic time frame, each moment an eternal present.

II. Language

Perspective is the myth of objective “distance.” As Rosalind Krauss remarked, in perspective and the visual domination that is its extension, it is an accepted contradiction that visual objectivity relies on subjectivity. Chung’s work is a contradiction, for it revives the remains of an arbitrarily ambiguous subject in linear perspective.

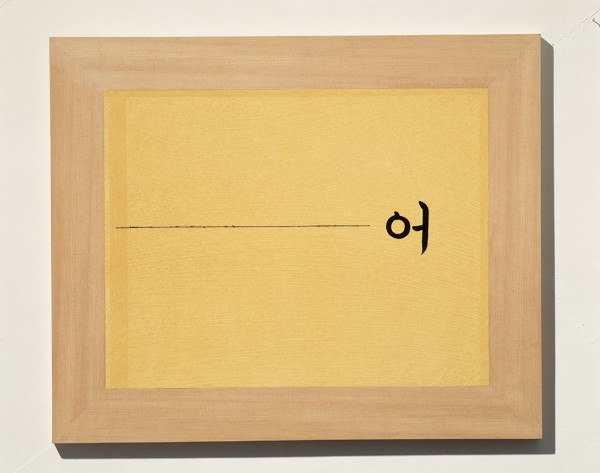

Chung has a dry way of expressing herself that confirms the impenetrability of language. Her works have commonplace themes—flowers, cars, waves, roads—and the language of her artistic intention is like murmurs brushing their surfaces lightly. Two Different Flowers, Vase with Road, Sculpture with Rubber Band and other titles are reasonable words that just don’t correspond to the objects in question, blocking us from penetrating their surfaces. Oasis isn’t an oasis, Athletic Flower Arrangement makes a strange association between art and sport. Chung spits out absurd words more cutting than black humor. A vinyl floor covering becomes a Ghost Will be Better, a used sponge The Sculpted Bride. A flower in a painting is made of Styrofoam, a landscape becomes an oasis, and, in one bound, an amusing Eiffel Tower becomes Tower.

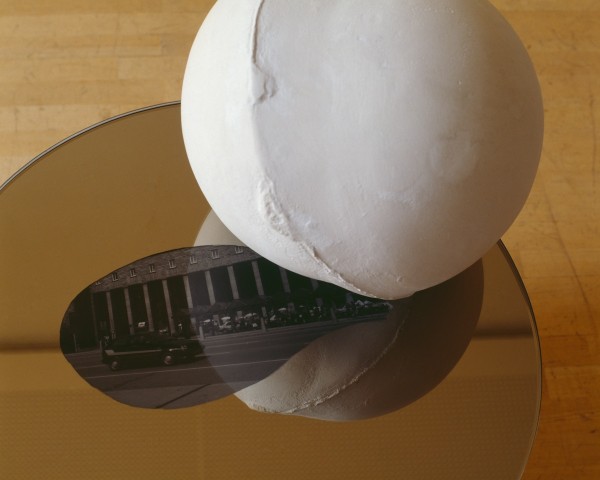

A list of her language would have to include the images and objects that the words describe and often betray. In a written landscape including drawing and sculpture, she etches a description on glass of a giant riding a scooter. She links drawing and painting to sculpture, and sculpture to furniture on which she inscribes words. She erases languages’ borders by mixing together different linguistic signs, or allowing them to escape from their former identities. The correspondence between signifier and signified collapses. The photo Railroad Station is the shadow of a sculpture; To Have to Have is a person and a drop of water; a ghost, a flame and a wave are one and the same form. Language, multiple and indeterminate, comes and goes between imaginative and real worlds. Her linguistic games liberate language from the chains of mathematical perspective and make fun of the vanity hidden in supposedly profound concepts.

III. Frame

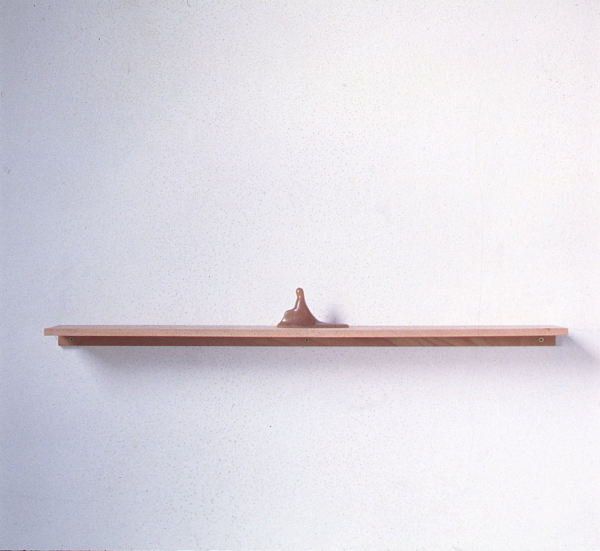

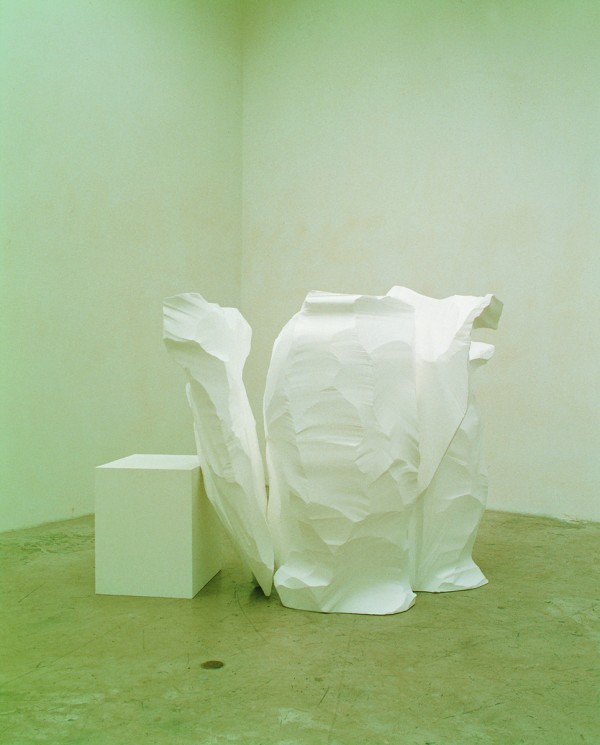

In the method and the matter, Chung makes no exceptions in hating “Depth.” She uses a real tree, sponge, Styrofoam, plasticine, glass, plaster, rags, even mint candy. Vinyl flooring or costume jewelry are, according to her, “imposing imitations.” She chooses materials contaminated by kitsch for the simple reason that kitsch is the fruit mass production. It breaks with the too-serious rhetoric of high culture and is her way of making fun of “artistic creation.” She reproduces well-known images, then has them refer to each other. Drawing and sculpture, sculpture and sculpture, painting and painting copy one another. A carbon copy of one of her own drawings is a new drawing that is both print and original, suggesting that the original hardy comes from the depths of the artistic mind, a shrewd move, for the breakdown between “artistic creation” and new reproduction techniques is a myth. She distances herself from masterpiece and the monument, frees herself from art versus non-art, high culture versus kitsch, and instead of “serious art,” prefers the light, the sterile and the boring, since the boring is closer to the truth.

IV. Parallelism in Depth

“When I see the open horizon, I’m not sure if it is a given that the two sides of the road converge nor that they are parallel. The two sides are “parallel” in “depth”…Depth…does not define the projection of a road in perspective nor the road itself.” (Maurice Merlot-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, 1962)

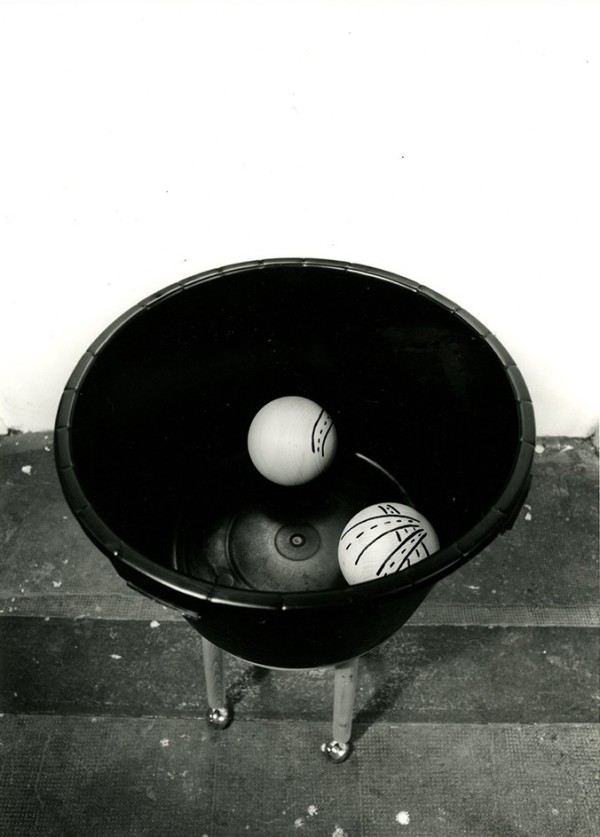

In Chung’s work, the theme of the road appears: The Road and especially Vase with Road, where the curving road follows the curving vase as if it sought to escape the flatness of Euclidian geometry. And like the curvature of the spinning earth that the geometrician claculates, Chung’s roads express curves that move, highways, parallel and painted in perspective on a wooden ball that remind us that depth and parallelism are not mutually exclusive. To avoid the eyes’ tyranny is not to blind oneself, and to wear feelers is but another tyranny. She adapts feelers only to escape the “Depth” that conditions the eyes.

What she hates, is not “Depth,” but the terms that go with it. True, “she avoids depth”; false, “her work has no depth.” Thinness, lightness and childishness avoid the weight of high and solemn culture, serious language and linear perspective. By balancing between seeing and feeling, the serious and the joke, sculpture and furniture, she erases boundaries. Although the words in her works are empty, they are right on target. Her use of kitsch is not a joke. She creates two flowers out of squeezed sponges, and sculpts waves with the craft of a traditional sculptor. By hesitating between empty space and linear perspective, Chung plays with floating signifiers that refuse to anchor themselves to a system. Sometimes by having them meet, sometimes by having them avoid each other, she adds a road or erases the one she just drew. These infinite possibilities for encounters are for her “the deep depth” that “avoids Depth.”